BES Photo 2007 prize exhibition (winner)

March>June 2008

Museu Colecção Berardo, Centro Cultural de Belém, Lisbon, Portugal

exhibited works:

- Liine, 7 Durst Lambda prints on aluminium,100×100cm each, 2008.

- Liine HD video, 5′00”, no audio. on plasma screen. 2008

- retarC, 4 Durst Lambda prints on aluminium,100×132cm each, 2008

- Planets, 8 Durst Lambda prints on aluminium, 100×133cm each, crop projectors. 2008.

.

Liine

retarC

Planets

Interview from the exhibition catalogue.

(scroll down for portuguese version)

A Suspension of Disbelief

A dialogue about the boundaries between representation, fiction, reality and originality.

Miguel Soares and Filipa Ramos

Filipa Ramos: I would like to know more about your training…

Miguel Soares: My contact with photography begins around 1985 at the Photography Club of the D. Pedro V high school in Lisbon. The club was oriented by professor Emilio Felício, who also taught chemistry, and it focused on the laboratory part in black-and-white, in other words, on the chemical side of photography.

In 1988 I enrolled in the Course of Photographic Studies at the Ar.Co.. During the first year I had Lúcia Vasconcelos as a teacher, which gave me a lot of enthusiasm, and the following year I had José Soudo, a great reference for all those who had him as a teacher. During that same year, which was an interim before entering the school of Fine Arts, I enrolled in a workshop of free drawing at the Monumental Gallery with the painter Manuel San Payo. At that time it was one of the most interesting and active galleries in Lisbon. It was when the photographer Álvaro Rosendo invited me to do an individual show. I was twenty years old and it was the beginning of an eleven-year relationship with that gallery.

In 1989 I entered the University of Fine Arts in Lisbon, were I got a degree in Equipment Design, on one hand to learn about different materials, and on the other because I didn’t want to spend five years painting and drawing, for I have been doing that since I was very young. What was important during this period was the creation of a group of friends, or it would have been an arduous experience. Among the members of that group were Miguel Mendonça (no longer with us), Tiago Batista, Alexandre Estrela, Nuno Silva, Pedro Cabral Santo, Rui Serra, Rui Toscano and Paulo Mendes. We soon began organizing collective shows in and outside the University. Exhibits like 1990, Faltam nove para 2000 or Wallmate (1995) in the University, Independent Worm Saloon at the Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes (1994), or O Império Contra-Ataca at the ZDB (1998); and Jamba (1997), Biovid (1998) and Espaço 1999, at the Sala do Veado, among others.

FR: Are there any coordinates that modelled your present work? I could identify certain elements, like a reflection on what is real, a link between music and images, and an analysis of the mechanisms that regulate and determine perception, but I would like to hear it from you …

MS: There are interests which are constant from the beginning, because I am almost always centred on investigation and experimentation, but I think my concerns have varied quite a lot over time. The sort of things I did in 1992 were already very different from what I’ve done the previous year, and I believe that it has always been a bit like that. Howevere, sometimes I like to recapitulate and to tackle questions that I can rethink or improve, either for technological reasons, due to time, or to other motives. It is extremely difficult for me to identify the connecting threads that have prevailed during all this time. As an example I do know that music only starts appearing directly in my work around 1994. In terms of photography, between 1990 and 1994, I was a lot more interested in iconology and symbolism than I am nowadays. I think that my interest in design and architecture, as man-made creations, together with science, have been the most constant elements in my work over the years.

FR: In fact, it is easy to recognize an interest for design and architecture, especially in the second half of the 1990’s, when you created objects like Racing (1994) or Beep (1998). In the same way, science seems to be a constant. I remember once Pedro Cabrita Reis said that he imagined you as one of those kids that were always playing with robots and carrying out chemistry experiments!

Sometimes your work seems to be made in order to underline its basic and curious elements. This can be seen thorough the repetition of certain aspects (like in Untitled (Playing with Gould Playing Bach), 2007). It also happens when you another element, like in Expecting to Fly (1999-2001), in which the music of Buffalo Springfield gives a certain poetic/ironic touch to the situation, absurd and surreal in itself, of an automobile accident on a road with no movement. In what way are you interested in revealing tiny details in daily practices, using a photographic frame?

MS: I’m not sure I worry about that, except in the sense of the punctum that Roland Barthes mentions, the discovery of some element in an image that makes it special.

But we can analyse that individually. The repetition of Glenn Gould’s video deals with the fact that I have read about him being autistic. I had already used some Gould piano samples in my music, and I started thinking that if I had an image to accompany it, his autism – which wasn’t at all clear to me – would become obvious, and that’s what I tried to do in this video. I decided to compose four themes of about two or three minutes each, based only on segments of six to ten seconds of the Brandenburg Concert No. 5, filmed in 1962. In total, I used more or less half a minute to produce ten minutes. I mounted the sound by doing hundreds of tiny little cuts, without paying attention to the image, that came by association, just as if I was mounting music using the “cut and paste” method in an audio programme.

Expecting to Fly was quite a different process. That scene was filmed in 1999 and I spent two years trying to figure out what to do with it. I knew I had to find the right music to follow up the other video that I had filmed on my balcony (Untitled (two), 1999), but I only made up my mind in 2001.

FR: Still talking about the use of apparently banal and daily elements, from which one can make new interpretations of what surround us, I would like to know a bit more about your new series Planets, (2008). In this case you used conventional photography to create a series of illusions that are unveiled as we pass through the images …

MS: My uncle illuminates his backyard with a series of round lights made in something that resembles Plexiglass. The lamp posts are about a meter high and the spheres are approximately twenty five centimetres. They are very old and you can notice it: some have moss, others have holes and cigarette burns, others have mud stains or insect debris, and some have yellowed. The type of light bulb used also varies, some are white or bluish and others are more yellow. What I did was to considerably close the diaphragm of the camera and photograph all the spheres from above, so that one couldn’t see the posts. They look like planets. Only at the end do I open slightly the diaphragm to reveal the mystery of a solar system that lies sleeping in my uncle’s yard.

FR: The craters and palindromes portray an almost puerile curiosity to test the reality of things, their possibility of existing in slightly altered conditions. Where is this interest or desire to investigate a subtly distorted reality coming from?

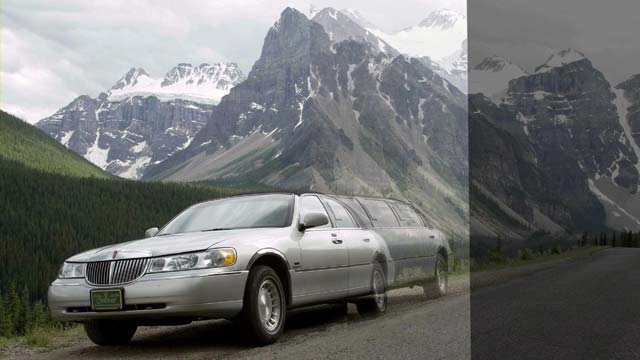

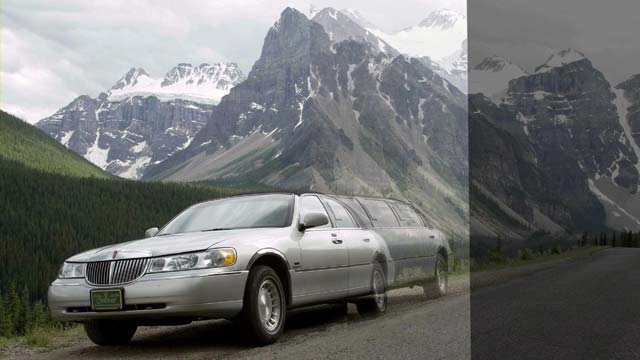

MS: I am quite interested in it. It is almost like a scientific process: the hypothesis is formulated and then a series of tests are carried out to prove it. That is what happens in the series with the limousines (Liine, 2007). Or, for example, in the series retarC (2007), in which I thought that if I turned a crater upside-down it would look like a plateau. This idea came to me when I saw pictures of underground explosions that created slight elevations on the surface. I experimented, and it worked with some of the craters. I realized that the light was crucial for creating this effect, and sometimes I inverted the image so that the light would come always from the left, making the illusion bigger.

FR: Sometimes you seem to take hold of the original images and alter them, recovering, let’s say, a certain primeval state of the elements represented. This is visible both in some of your earlier pieces, and recently in the series where you “remove” a part which had actually been an addition, giving back a more conventional look to the automobile (Liine). How do you characterize this interest in manipulating reality through photography?

MS: The case of the limousines had been in my head for over ten years because they look like normal cars that have been artificially stretched in a Photoshop, (the first ones I saw where on television and in magazines). I did this series mainly to satisfy my curiosity – how would the backgrounds look? Would the car seem like a normal car? Of course, there are second meanings: a shortening of distances, an appeal to slow down, environmental issues, an anti nouveau riche feeling, the effect of teleportation created by the transition of before and after the cut (visible in the Liine video, 2007). But all these interpretations depend on who is seeing it.

FR: I find a similar attitude in Untitled (playing with Gould playing Bach) in which the chosen frames gained a certain suspension, between a movement and a static side, which characterizes all the representations of passed, and unrepeatable, elements. You appear to take photographs through the annulation the image’s movement in time. In what way can a picture result from video?

MS: As I explained previously, I fragemented small portions of the concert into hundreds of slices, sometimes in one, two or three frames, and with them I tried to compose music. The fact that each second of film consisted of twenty four photographs (photograms), or twenty five in the case of television or PAL video, enabled each photograph to be accompanied by a moment of sound with a certain duration – in cinema, 41,66 thousandths of a second of sound. This amount of time is more than enough to work with and, even eventually to stretch it in audio editing programes. If the sound is at 48KHz, it can still be divided into two thousand smaller slices. This arouses my curiosity about the sound of a specific photograms that were filmed.

FR: In this same video there is a characteristic, which is very present in your work – the relation between image and music. How do you articulate these two elements and how do they coexist?

MS: The combination of sound and image is, normally, one of those cases in which the whole is more than the sum of its parts. I think I have used it in a very different way in each work.

Sometimes the audio is used to increase the power of immersion of a given video, even to increase the realism. It can carry a more important message than the image, or it can simply be used to create an atmosphere. It can also be used to change the meaning of the image. There is also music that I edit on CD and for which I create series of images or videos. There were cases in which I felt the necessity to illustrate a certain music, either mine or someone else’s, with images.

I think I use music and audio in different ways and with different functions.

FR: Many of your pieces use elements that touch on the copyright issue and raise questions about the crisis of the current concept of intellectual property. What is your feeling about these problems?

MS: It is a very complex issue of our times, in which we are surrounded by images, sounds, and words that belong to companies, while art continues needing the world around itself as raw material. Originally copyright served to stimulate literary creativity, and had a short period of duration, after which the creation entered public domain and became much more affordable. Up to the middle of the last century, classical music, blues, and a lot of other music only existed thanks to the recycling of musical heritage. A lot of modern music would never exist if it were necessary to ask all the authors for authorization for samples (sometimes hundreds of them).

I believe that each case need to be individually analyzed. I think that the question should be raised only when profits that belong to the original author are being misappropriated. Not when we use a small part to comment, critique or pay homage, as a form of art. That is, when Richard Prince used the images of the Marlboro Man in the 1970’s, he was in no way competing with Marlboro to sell cigarettes! By the same token, if I use a phrase of Michael Jackson for a musical composition, I’m not selling it as if it was his creation. Therefore, no one will stop buying his records because of mine.

FR: You often use digitally constructed images, such as the series of inverted craters, RetarC, or the two videos Place in Time (2005), Sparky (2002) or H2O (2004). In what way are you interested in photography as a means to construct possible inexistent realities?

MS: For me, photojournalism is an example of how photography can construct reality. The pictures that appear in the newspapers and illustrate our recent history, are, to a greater or lesser degree, premeditated. Even if I find this aspect interesting, I believe that in most cases I belong to the opposite field, using images to construct fiction.

FR: More than using 3D to explore a new media, (and such was the case of digital format when you started using it in the 1990’s), you seem to use it to create photographic situations that you don’t have access to. By this train of thought, these images become digital photographs, also dependent on the photographer’s choice of an exact, unique moment, in which they are captured and crystallised. Do you see your images as photographs or are they closer to traditional pictorial representation, like painting or drawing?

MS: Quite true. I undoubtedly see digital images as photography. In the case of 3D animation, which is closer to the concept of cinematic photography, all the concerns that we must have with these, (and many more), are the same ones we have in 3D: the choice of a lens, the angle, the lighting, etc.. If the scene is static, the moment is no longer crucial and we find ourselves in a photograph in which the moment is everywhere. In 3D, a universe (or theatre) is created for each scene, and that would be impossible in the real world. And I depend on absolutely no one to do it, which is a relief. I can have an enormous city on top of a slice of pizza, and go in through a window of one of the buildings, go to the kitchen and find another slice of pizza on top of the table with another city on top.

I am also interested in this fractional side because it is very close to the tools provided by nature, which makes 3D for me, something that is natural and not artificial. I would dare to say that it seems less artificial than painting on a canvas.

FR: A phrase of Roland Barthes in Câmara Lucida, in which he refers that cinema is never a hallucination but just an illusion; his vision is oneiric and not ecmenesic, made me think of your work. Do you share this point of view in regard to your relationship between what you create and the elements you use as a starting point?

MS: I think that in cinema ecmenesia occurs when we see a film and establish our keyframes. The remains are not the sequence but certain scenes and key points that vary from person to person. But our will to accept illusion, even in unlikely and technically imperfect cases, like the cinema of Ed Wood, the so called Suspension of Disbelief theory, interests me very much. There are things that when we watched twenty years ago seemed highly credible and realistic and that nowadays are simply obsolete. In other cases this doesn’t occur. The theory of the Suspension of Disbelief lead us to both immerse in a film of Ed Wood as it allow us to believe in the exemption of the documentaries of Frederick Wiseman. It is an elastic force, which is also transformed according to our prejudices about what we see. If we want to believe, we do.

-

Portuguese version

A Suspension of Disbelief

Um diálogo sobre as fronteiras entre representação, ficção, realidade e originalidade.

Miguel Soares e Filipa Ramos

Filipa Ramos: Eu gostava de saber mais sobre a tua formação.

Miguel Soares: A minha ligação à fotografia começa por volta de 1985 no Núcleo de Fotografia do Liceu D. Pedro V em Lisboa. O núcleo era coordenado pelo professor Emílio Felício, também professor de química e era centrado na parte de laboratório a preto e branco, ou seja, na parte química da fotografia.

Em 1988 inscrevi-me no Plano de Estudos de Fotografia do Ar.Co. No primeiro ano tive como professora a Lúcia Vasconcelos, que me deu bastante entusiasmo, e no segundo ano tive o José Soudo, uma referência para todos os que por ele passaram. Durante esse mesmo ano, que foi um compasso de espera para entrar nas Belas Artes, inscrevi-me também num Atelier Livre de Desenho na Galeria Monumental com o pintor Manuel San Payo. Nessa altura, era uma das galerias mais interessantes e activas de Lisboa. Foi quando o fotógrafo Álvaro Rosendo me convidou para fazer uma exposição individual. Eu tinha vinte anos e foi o início de uma relação de onze anos com a Monumental.

Em 1989 entrei para a Faculdade de Belas Artes de Lisboa, onde fiz a licenciatura em Design de Equipamento. Por um lado para aprender sobre os materiais e, por outro, porque não estava com vontade de passar cinco anos a pintar e a desenhar, coisa que já fazia desde pequeno. Aífoi importantíssimo ter-se criado um grupo de amigos, de outro modo teria sido uma experiência penosa. Desse grupo faziam parte o Miguel Mendonça (já desaparecido), Tiago Batista, Alexandre Estrela, Nuno Silva, Pedro Cabral Santo, Rui Serra, Rui Toscano e Paulo Mendes. Rapidamente começámos a organizar exposições colectivas dentro e fora da faculdade. Exposições como 1990, Faltam nove para 2000 ou Wallmate (1995) dentro da Faculdade, Independent Worm Saloon na Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes (1994), ou O Império Contra-Ataca na ZDB (1998); e Jamba (1997), Biovoid (1998) e Espaço 1999, na Sala do Veado, entre outras.

FR: Existem coordenadas que foram dando forma ao que é o teu trabalho actual? Poderia identificar certos elementos, como uma reflexão sobre o real, uma ligação estreita entre a música e as imagens e uma análise dos mecanismos que regulam e determinam a percepção, mas gostava de saber por ti…

MS: Existem pesquisas constantes desde o início, porque o meu interesse está quase sempre centrado nos actos de pesquisar e experimentar, mas julgo que as minhas preocupações foram variando bastante ao longo dos tempos. O tipo de coisas que fazia em 1992 já era muito diferente do que tinha feito no ano anterior e julgo que tem sido sempre um pouco assim, embora às vezes goste de voltar atrás e voltar a pegar em questões que posso repensar ou melhorar, seja por questões tecnológicas, por questões de tempo ou por outros motivos.

É para mim extremamente difícil identificar fios condutores que se tenham mantido ao longo do tempo. Sei, por exemplo, que a música só começa a aparecer directamente no meu trabalho por volta de 1994. No que diz respeito à fotografia, entre 1990 e 1994 estava bastante mais interessado em iconologia e simbolismo do que hoje em dia. Penso que o meu interesse pelo design e pela arquitectura, como criações do homem, juntamente com a ciência, tenham sido as principais constantes no meu trabalho ao longo destes anos.

FR: De facto é fácil de identificar um interesse pelo design e pela arquitectura, sobretudo na segunda metade dos anos 90, quando realizaste objectos como Racing (1994) ou Beep (1998). Do mesmo modo, a ciência parece ser uma constante. Lembro-me de uma vez o Pedro Cabrita Reis ter dito que te imaginava como uma daquelas crianças que estavam sempre a brincar com robôs e a fazer experiências de química!

Por vezes as tuas obras parecem ser criadas de modo a pôr em evidência os seus elementos mais básicos ou curiosos, seja através da repetição exaustiva de certos aspectos (como em Untitled (Playing with Gould Playing Bach), 2007); seja através da adição de outro elemento, como em Expecting to Fly (1999-2001), em que a música dos Buffalo Springfield confere um certo toque poético/irónico à situação, já por si absurda e surreal, de um despiste de um automóvel numa estrada sem movimento. De que modo é que te interessa revelar o particular dentro do corriqueiro, usando um suporte fotográfico?

MS: Não sei se sinto isso como preocupação a não ser no sentido do punctum que Roland Barthes refere, ou seja descobrir algo na imagem que a torna especial.

Mas podemos ver caso a caso. A repetição do vídeo do Glenn Gould, tem a ver com eu ter lido sobre ele ser autista. Já tinha usado samples de piano do Gould nas minhas músicas, e fiquei a pensar que se tivesse a imagem a acompanhar, o seu autismo – que para mim não era nada evidente – se tornaria óbvio, e foi isso que tentei fazer neste vídeo. Resolvi compor quatro temas de cerca de dois, três minutos cada, apenas com base em segmentos de seis a dez segundos do Concerto de Brandenburgo n.º 5, filmado em 1962. No total usei cerca de meio minuto para fazer dez minutos. Através de centenas cortes minúsculos, montei o som sem prestar atenção à parte da imagem que vinha por arrasto, tal qual estivesse a montar música pelo método de “corta e cola” num programa de áudio.

Em relação ao Expecting to Fly foi bem diferente. A cena foi filmada em 1999 e andei dois anos a tentar descobrir o que fazer com ela. Sabia que devia procurar a musica certa para vir no seguimento de outro vídeo que tinha filmado da minha varanda (Untitled (two), 1999), mas só em 2001 é que me decidi.

FR: Ainda dentro desde uso de elementos aparentemente banais e quotidianos, para a partir deles gerar novas leituras daquilo que nos rodeia, gostaria de saber um pouco mais sobre a tua nova série Planets, (2008). Neste caso recorreste à fotografia convencional para gerar uma série de ilusões que vão sendo desvendadas à medida que vamos percorrendo as imagens…

MS: Um tio meu tem a iluminar o quintal das traseiras da sua casa uma série de candeeiros esféricos num material tipo Plexiglas. Os pés têm cerca de um metro de altura e as esferas terão um diâmetro de cerca de 25 cm. São já muito velhos e as esferas têm uma variedade de marcas do tempo: umas têm musgo, outras estão furadas ou queimadas por cigarros, outras têm manchas de lama ou dejectos de insectos, algumas estão amarelecidas. O tipo de lâmpada usada também varia, apresentando-se umas mais brancas ou azuladas e outras mais amareladas. O que fiz foi fechar bastante o diafragma da câmara e fotografar todas as esferas de cima para baixo para que não se visse o pé. Parecem planetas. Só no final abro um pouco o diafragma para revelar o mistério de um sistema solar que repousava adormecido no quintal do meu tio.

FR: Nas crateras e nos palindromos emerge uma curiosidade quase pueril de testar a realidade das coisas, a sua possibilidade de existência em condições ligeiramente alteradas. Em que reside este interesse ou esta pesquisa por esta realidade subtilmente distorcida?

MS: Interessa-me bastante. Quase como método científico: há a formulação de uma hipótese e depois o efectuar de uma série de testes para a comprovar. Assim se passa na série das limusinas (Liine, 2007). Ou, por exemplo, na série retarC (2007), em que pensei que se virasse a imagem de uma cratera ao contrário ela iria parecer um planalto. Esta ideia surgiu-me ao ver imagens de explosões subterrâneas, que criavam pequenos altos à superfície. Fiz a experiência e resultou com algumas das crateras. Vi que a luz era determinante para a criação deste efeito e, por vezes, inverti a imagem para a luz vir sempre da esquerda e a ilusão ser maior.

FR: Por vezes pareces pegar nas imagens originais para depois as alterares, recuperando, digamos, um certo estado primordial da condição dos elementos representados. Isto é não só visível em algumas obras mais antigas, como também, recentemente, na série em que lhes “retiras” um pedaço, que já por si era um acrescento, voltando a dar ao automóvel o seu aspecto mais convencional (Liine). Como caracterizas este interesse pela manipulação da realidade através da fotografia?

MS: O caso das limusinas andava na minha cabeça há mais de dez anos, pelo facto de parecerem carros normais que foram artificialmente esticados no Photoshop (isto porque as primeiras limusinas que vi foi na TV ou em revistas). Fiz a série sobretudo para satisfazer a minha curiosidade – Como ficariam os fundos? O carro iria parecer um carro normal? Claro que há segundas leituras: o encurtar as distâncias, um apelo ao abrandamento, questões ecológicas, anti novo-riquismo, o efeito de teletransporte criado pela transição entre o antes e o depois do corte (visível no vídeo Liine, 2007). Mas estas leituras já dependem de quem vê.

FR: Encontro uma atitude semelhante em Untitled (playing with Gould playing Bach) em que fizeste com que os frames escolhidos ganhassem uma certa suspensão entre um movimento e um lado estático, que caracteriza todas as representações de elementos passados e, logo, irrepetíveis. Pareces fotografar através da anulação do tempo da imagem em movimento. De que modo é que a fotografia pode decorrer do vídeo?

MS: Como expliquei anteriormente, pequenas porções do concerto foram fragmentadas em centenas de fatias por vezes de um, dois ou três frames, e com eles tentei compor música. O facto de cada segundo de filme ser composto por vinte e quatro fotografias (fotogramas), ou vinte e cinco no caso da televisão e do vídeo PAL, faz com que cada fotografia seja acompanhada de um momento de som com uma duração certa, em cinema são 41,66 milésimos de segundo de som. É tempo mais que suficiente para trabalhar e, eventualmente, esticar em programas de edição de áudio. Se o som estiver a 48KHz ele ainda poderá ser dividido em duas mil fatias mais finas. Isto desperta a minha curiosidade pelo som de fotogramas específicos de momentos filmados.

FR: Neste mesmo vídeo está presente uma característica muito presente no teu trabalho, a relação entre a imagem e a música. De que modo é que estes dois elementos se articulam e convivem?

MS: O conjunto som e imagem é, normalmente, um daqueles casos em que o todo é mais do que a soma das partes. Julgo que o tenho usado de formas muito diversas de trabalho para trabalho.

Por vezes o áudio é usado para aumentar o poder de imersão de determinado vídeo, até mesmo para aumentar o realismo. Pode conter uma mensagem mais importante do que a imagem, ou pode apenas servir para criar um ambiente. Pode também ser usado para mudar o significado da imagem. Depois há as músicas que edito em CD e para as quais faço séries de imagens ou vídeos. Houve casos em que senti a necessidade de ilustrar determinada música, seja minha ou de outros, com imagens.

Portanto julgo que uso a música e o áudio de diversas formas e com diversas funções.

FR: Muitas das tuas obras utilizam elementos que tocam a questão do copyright e que abordam questões que realçam a crise do modelo actual da propriedade intelectual. Qual é a tua relação com estes problemas?

MS: É uma questão muito complexa decorrente de hoje em dia estarmos rodeados de imagens, sons e palavras que pertencem a empresas e da necessidade da arte continuar a precisar do mundo à sua volta como matéria prima. O copyright na sua origem servia para estimular a criação literária e tinha um período de duração curto, a partir do qual as criações entravam em domínio público e tornavam-se muito mais baratas. A música clássica, os Blues e muita da música até meados do século passado só existiu graças à reutilização de heranças musicais. Muitas das músicas feitas actualmente nunca existiriam se se tivesse de pedir autorização a todos os autores pelos samples (por vezes centenas).

Julgo que é preciso analisar caso a caso. Penso que só se deveria levantar a questão quando se estão mesmo a desviar lucros que pertencem ao autor original. Não quando se usa uma pequena porção para comentar, criticar ou homenagear, sob a forma de arte. Ou seja, quando nos anos 70 o Richard Prince utilizou as imagens do Marlboro Man, não estava de modo nenhum a concorrer com a Marlboro na venda de cigarros! Da mesma forma que se usar uma frase do Michael Jackson numa música, não estou a vender a musica como se fosse da autoria dele, logo ninguém vai deixar de lhe comprar os discos por causa do meu.

FR: Recorres frequentemente ao uso de imagens construídas digitalmente, como é o caso da série das crateras invertidas, RetarC, ou dos vídeos Place in Time (2005), Sparky ou H2O (2004). De que modo é que a fotografia te interessa como um mecanismo de construção de possíveis realidades inexistentes?

MS: Para mim, um exemplo de fotografia como construção da realidade é o fotojornalismo. Ou seja, as imagens que aparecem nos jornais e que acabam por ilustrar a nossa história recente de uma forma, umas vezes mais, outras vezes menos, premeditada. Embora também isso me interesse muito, julgo que na maioria dos casos me encontro no campo oposto, usando a imagem para construir ficções.

FR: Mais do que utilizar o 3D para explorar um suporte novo, como era o formato digital quando começaste a usá-lo nos anos 90, parece que o usas para criares fotograficamente situações que não tens à tua disposição. Estas imagens tornam-se dentro desta lógica, fotografias digitais também elas dependentes da escolha do fotógrafo de um momento exacto, único, em que foram capturadas e cristalizadas. Vês as tuas imagens como fotografias ou mais próximas da representação pictórica tradicional, como a pintura e o desenho?

MS: É bem verdade. Vejo as imagens digitais como fotografia sem dúvida. E, no caso das animações 3D, mais próximas do conceito de fotografia de cinema, pois todas as preocupações desta (e muitas mais) estão presentes no 3D: a escolha da lente, a tomada de um ponto de vista, a iluminação, etc. Se a cena for estática o momento deixa de ser crucial, e passamos a estar dentro de uma fotografia, em que o momento está por todo o lado. No 3D para cada cena cria-se um universo (ou um teatro) que seria impossível no mundo real. E não estou dependente de absolutamente ninguém para o fazer. Isso deixa-me descansado.

Posso ter uma cidade enorme em cima de uma fatia de pizza e entrar numa janela de um dos prédios, ir à cozinha e encontrar outra fatia de pizza em cima da mesa com outra cidade em cima. Há este lado fractal que também me interessa porque está muito próximo das ferramentas que a natureza tem à disposição, o que faz com que para mim o 3D não me pareça uma coisa de todo artificial, mas sim natural. Quase diria que me parece menos artificial do que pintar numa tela.

FR: Uma frase de Roland Barthes, no Câmara Clara, em que ele refere que o cinema nunca é uma alucinação, mas apenas uma ilusão; a sua visão é onirica e não ecmenésica, fez-me pensar no teu trabalho. Partilhas deste ponto de vista no que respeita à tua relação entre o que crias e os elementos que tomas como ponto de partida?

MS: No cinema julgo que a ecmenésia se dá quando vemos o filme e estabelecemos os nossos keyframes. O que fica não é a sequência, mas sim algumas cenas e pontos-chave que variam de pessoa para pessoa. Mas a nossa vontade de aceitar a ilusão, mesmo em casos inverosímeis e tecnicamente imperfeitos como no cinema de Ed Wood, a chamada teoria da Suspension of Disbelief interessa-me imenso. Há coisas que víamos há vinte anos atrás e pareciam altamente verosímeis e realistas e que hoje em dia parecem muito mal feitas. Noutros casos, isso não acontece. A teoria da Suspension of Disbelief tanto nos leva a imergir num filme do Ed Wood, como a acreditar na isenção dos documentários de Frederick Wiseman. É uma força elástica que também se transforma de acordo com os nossos preconceitos sobre aquilo que vemos. Se queremos acreditar, acreditamos.

Filipa Ramos: I would like to know more about your training…

Miguel Soares: My contact with photography begins around 1985 at the Photography Club of the D. Pedro V high school in Lisbon. The club was oriented by professor Emilio Felício, who also taught chemistry, and it focused on the laboratory part in black-and-white, in other words, on the chemical side of photography.

In 1988 I enrolled in the Course of Photographic Studies at the Ar.Co.. During the first year I had Lúcia Vasconcelos as a teacher, which gave me a lot of enthusiasm, and the following year I had José Soudo, a great reference for all those who had him as a teacher. During that same year, which was an interim before entering the school of Fine Arts, I enrolled in a workshop of free drawing at the Monumental Gallery with the painter Manuel San Payo. At that time it was one of the most interesting and active galleries in Lisbon. It was when the photographer Álvaro Rosendo invited me to do an individual show. I was twenty years old and it was the beginning of an eleven-year relationship with that gallery.

In 1989 I entered the University of Fine Arts in Lisbon, were I got a degree in Equipment Design, on one hand to learn about different materials, and on the other because I didn’t want to spend five years painting and drawing, for I have been doing that since I was very young. What was important during this period was the creation of a group of friends, or it would have been an arduous experience. Among the members of that group were Miguel Mendonça (no longer with us), Tiago Batista, Alexandre Estrela, Nuno Silva, Pedro Cabral Santo, Rui Serra, Rui Toscano and Paulo Mendes. We soon began organizing collective shows in and outside the University. Exhibits like 1990, Faltam nove para 2000 or Wallmate (1995) in the University, Independent Worm Saloon at the Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes (1994), or O Império Contra-Ataca at the ZDB (1998); and Jamba (1997), Biovid (1998) and Espaço 1999, at the Sala do Veado, among others.

FR: Are there any coordinates that modelled your present work? I could identify certain elements, like a reflection on what is real, a link between music and images, and an analysis of the mechanisms that regulate and determine perception, but I would like to hear it from you …

MS: There are interests which are constant from the beginning, because I am almost always centred on investigation and experimentation, but I think my concerns have varied quite a lot over time. The sort of things I did in 1992 were already very different from what I’ve done the previous year, and I believe that it has always been a bit like that. Howevere, sometimes I like to recapitulate and to tackle questions that I can rethink or improve, either for technological reasons, due to time, or to other motives. It is extremely difficult for me to identify the connecting threads that have prevailed during all this time. As an example I do know that music only starts appearing directly in my work around 1994. In terms of photography, between 1990 and 1994, I was a lot more interested in iconology and symbolism than I am nowadays. I think that my interest in design and architecture, as man-made creations, together with science, have been the most constant elements in my work over the years.

FR: In fact, it is easy to recognize an interest for design and architecture, especially in the second half of the 1990’s, when you created objects like Racing (1994) or Beep (1998). In the same way, science seems to be a constant. I remember once Pedro Cabrita Reis said that he imagined you as one of those kids that were always playing with robots and carrying out chemistry experiments!

Sometimes your work seems to be made in order to underline its basic and curious elements. This can be seen thorough the repetition of certain aspects (like in Untitled (Playing with Gould Playing Bach), 2007). It also happens when you another element, like in Expecting to Fly (1999-2001), in which the music of Buffalo Springfield gives a certain poetic/ironic touch to the situation, absurd and surreal in itself, of an automobile accident on a road with no movement. In what way are you interested in revealing tiny details in daily practices, using a photographic frame?

MS: I’m not sure I worry about that, except in the sense of the punctum that Roland Barthes mentions, the discovery of some element in an image that makes it special.

But we can analyse that individually. The repetition of Glenn Gould’s video deals with the fact that I have read about him being autistic. I had already used some Gould piano samples in my music, and I started thinking that if I had an image to accompany it, his autism – which wasn’t at all clear to me – would become obvious, and that’s what I tried to do in this video. I decided to compose four themes of about two or three minutes each, based only on segments of six to ten seconds of the Brandenburg Concert No. 5, filmed in 1962. In total, I used more or less half a minute to produce ten minutes. I mounted the sound by doing hundreds of tiny little cuts, without paying attention to the image, that came by association, just as if I was mounting music using the “cut and paste” method in an audio programme.

Expecting to Fly was quite a different process. That scene was filmed in 1999 and I spent two years trying to figure out what to do with it. I knew I had to find the right music to follow up the other video that I had filmed on my balcony (Untitled (two), 1999), but I only made up my mind in 2001.

FR: Still talking about the use of apparently banal and daily elements, from which one can make new interpretations of what surround us, I would like to know a bit more about your new series Planets, (2008). In this case you used conventional photography to create a series of illusions that are unveiled as we pass through the images …

MS: My uncle illuminates his backyard with a series of round lights made in something that resembles Plexiglass. The lamp posts are about a meter high and the spheres are approximately twenty five centimetres. They are very old and you can notice it: some have moss, others have holes and cigarette burns, others have mud stains or insect debris, and some have yellowed. The type of light bulb used also varies, some are white or bluish and others are more yellow. What I did was to considerably close the diaphragm of the camera and photograph all the spheres from above, so that one couldn’t see the posts. They look like planets. Only at the end do I open slightly the diaphragm to reveal the mystery of a solar system that lies sleeping in my uncle’s yard.

FR: The craters and palindromes portray an almost puerile curiosity to test the reality of things, their possibility of existing in slightly altered conditions. Where is this interest or desire to investigate a subtly distorted reality coming from?

MS: I am quite interested in it. It is almost like a scientific process: the hypothesis is formulated and then a series of tests are carried out to prove it. That is what happens in the series with the limousines (Liine, 2007). Or, for example, in the series retarC (2007), in which I thought that if I turned a crater upside-down it would look like a plateau. This idea came to me when I saw pictures of underground explosions that created slight elevations on the surface. I experimented, and it worked with some of the craters. I realized that the light was crucial for creating this effect, and sometimes I inverted the image so that the light would come always from the left, making the illusion bigger.

FR: Sometimes you seem to take hold of the original images and alter them, recovering, let’s say, a certain primeval state of the elements represented. This is visible both in some of your earlier pieces, and recently in the series where you “remove” a part which had actually been an addition, giving back a more conventional look to the automobile (Liine). How do you characterize this interest in manipulating reality through photography?

MS: The case of the limousines had been in my head for over ten years because they look like normal cars that have been artificially stretched in a Photoshop, (the first ones I saw where on television and in magazines). I did this series mainly to satisfy my curiosity – how would the backgrounds look? Would the car seem like a normal car? Of course, there are second meanings: a shortening of distances, an appeal to slow down, environmental issues, an anti nouveau riche feeling, the effect of teleportation created by the transition of before and after the cut (visible in the Liine video, 2007). But all these interpretations depend on who is seeing it.

FR: I find a similar attitude in Untitled (playing with Gould playing Bach) in which the chosen frames gained a certain suspension, between a movement and a static side, which characterizes all the representations of passed, and unrepeatable, elements. You appear to take photographs through the annulation the image’s movement in time. In what way can a picture result from video?

MS: As I explained previously, I fragemented small portions of the concert into hundreds of slices, sometimes in one, two or three frames, and with them I tried to compose music. The fact that each second of film consisted of twenty four photographs (photograms), or twenty five in the case of television or PAL video, enabled each photograph to be accompanied by a moment of sound with a certain duration – in cinema, 41,66 thousandths of a second of sound. This amount of time is more than enough to work with and, even eventually to stretch it in audio editing programes. If the sound is at 48KHz, it can still be divided into two thousand smaller slices. This arouses my curiosity about the sound of a specific photograms that were filmed.

FR: In this same video there is a characteristic, which is very present in your work – the relation between image and music. How do you articulate these two elements and how do they coexist?

MS: The combination of sound and image is, normally, one of those cases in which the whole is more than the sum of its parts. I think I have used it in a very different way in each work.

Sometimes the audio is used to increase the power of immersion of a given video, even to increase the realism. It can carry a more important message than the image, or it can simply be used to create an atmosphere. It can also be used to change the meaning of the image. There is also music that I edit on CD and for which I create series of images or videos. There were cases in which I felt the necessity to illustrate a certain music, either mine or someone else’s, with images.

I think I use music and audio in different ways and with different functions.

FR: Many of your pieces use elements that touch on the copyright issue and raise questions about the crisis of the current concept of intellectual property. What is your feeling about these problems?

MS: It is a very complex issue of our times, in which we are surrounded by images, sounds, and words that belong to companies, while art continues needing the world around itself as raw material. Originally copyright served to stimulate literary creativity, and had a short period of duration, after which the creation entered public domain and became much more affordable. Up to the middle of the last century, classical music, blues, and a lot of other music only existed thanks to the recycling of musical heritage. A lot of modern music would never exist if it were necessary to ask all the authors for authorization for samples (sometimes hundreds of them).

I believe that each case need to be individually analyzed. I think that the question should be raised only when profits that belong to the original author are being misappropriated. Not when we use a small part to comment, critique or pay homage, as a form of art. That is, when Richard Prince used the images of the Marlboro Man in the 1970’s, he was in no way competing with Marlboro to sell cigarettes! By the same token, if I use a phrase of Michael Jackson for a musical composition, I’m not selling it as if it was his creation. Therefore, no one will stop buying his records because of mine.

FR: You often use digitally constructed images, such as the series of inverted craters, RetarC, or the two videos Place in Time (2005), Sparky (2002) or H2O (2004). In what way are you interested in photography as a means to construct possible inexistent realities?

MS: For me, photojournalism is an example of how photography can construct reality. The pictures that appear in the newspapers and illustrate our recent history, are, to a greater or lesser degree, premeditated. Even if I find this aspect interesting, I believe that in most cases I belong to the opposite field, using images to construct fiction.

FR: More than using 3D to explore a new media, (and such was the case of digital format when you started using it in the 1990’s), you seem to use it to create photographic situations that you don’t have access to. By this train of thought, these images become digital photographs, also dependent on the photographer’s choice of an exact, unique moment, in which they are captured and crystallised. Do you see your images as photographs or are they closer to traditional pictorial representation, like painting or drawing?

MS: Quite true. I undoubtedly see digital images as photography. In the case of 3D animation, which is closer to the concept of cinematic photography, all the concerns that we must have with these, (and many more), are the same ones we have in 3D: the choice of a lens, the angle, the lighting, etc.. If the scene is static, the moment is no longer crucial and we find ourselves in a photograph in which the moment is everywhere. In 3D, a universe (or theatre) is created for each scene, and that would be impossible in the real world. And I depend on absolutely no one to do it, which is a relief. I can have an enormous city on top of a slice of pizza, and go in through a window of one of the buildings, go to the kitchen and find another slice of pizza on top of the table with another city on top.

I am also interested in this fractional side because it is very close to the tools provided by nature, which makes 3D for me, something that is natural and not artificial. I would dare to say that it seems less artificial than painting on a canvas.

FR: A phrase of Roland Barthes in Câmara Lucida, in which he refers that cinema is never a hallucination but just an illusion; his vision is oneiric and not ecmenesic, made me think of your work. Do you share this point of view in regard to your relationship between what you create and the elements you use as a starting point?

MS: I think that in cinema ecmenesia occurs when we see a film and establish our keyframes. The remains are not the sequence but certain scenes and key points that vary from person to person. But our will to accept illusion, even in unlikely and technically imperfect cases, like the cinema of Ed Wood, the so called Suspension of Disbelief theory, interests me very much. There are things that when we watched twenty years ago seemed highly credible and realistic and that nowadays are simply obsolete. In other cases this doesn’t occur. The theory of the Suspension of Disbelief lead us to both immerse in a film of Ed Wood as it allow us to believe in the exemption of the documentaries of Frederick Wiseman. It is an elastic force, which

is also transformed according to our prejudices about what we see. If we want to believe, we do.