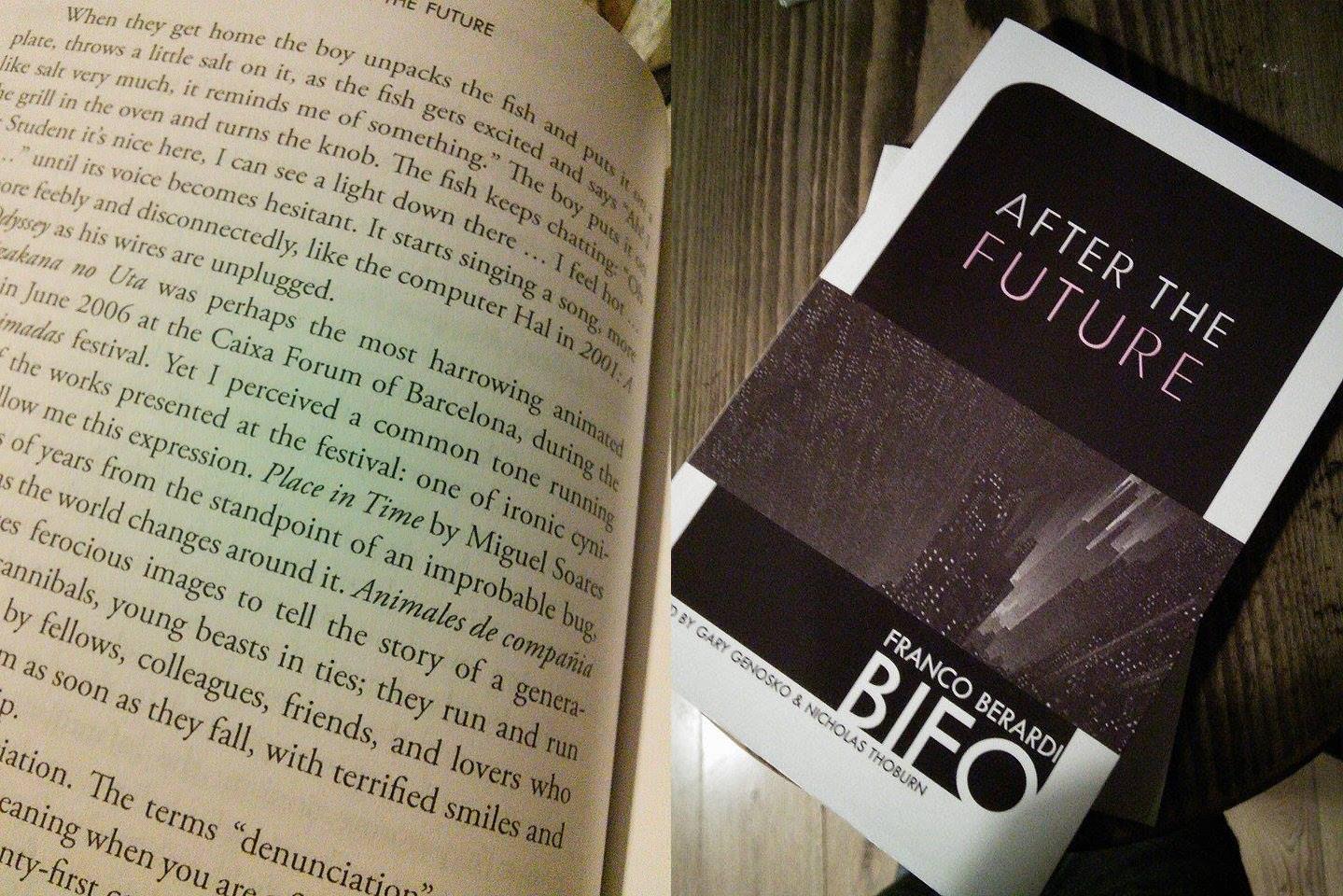

After the Future, Franco Bifo Berardi

Reference to Place in Time animation.

on After the Future, Franco Bifo Berardi, 2011, Gary Genosko Editor.

miguel soarestexts |

||

SearchCategories

most viewed |

After the Future, Franco Bifo Berardi2011.Sep

Reference to Place in Time animation.

Velocidad de Luz Variable, Biblioteca Histórica de la Universidad Complutense, Madrid2009.May

Velocidad de Luz Variable, Madrid May 23 > 29, 2009 exhibited works: related links: Velocidad de Luz Variable at visual-ma.com . (…) O último autor deste alinhamento, Miguel Soares, é um artista que desde sempre acompanho e com o qual divido atelier/ Oporto. Para além destes dados pessoais que tornam a minha escolha claramente facciosa, Miguel Soares é um pioneiro na criação meticulosa de universos digitais.

Geolux, Centro de Artes Visuais, Coimbra2009.Apr

solo show April > June 2009 list of works: video

prints

other . A exposição ”Geolux” de Miguel Soares surge no contexto do programa que o Centro de Artes Visuais – Encontros de Coimbra tem fomentado de divulgação da obra de artistas portugueses a meio de carreira com projectos pensados especificamente para esta instituição. Com um percurso iniciado no princípio dos anos 90, Miguel Soares (Lisboa, 1970) tem vindo a desenvolver um trabalho que se centra em preocupações relacionadas com a tecnologia e a criação humana (onde a ficção científica tem particular relevo), a relação entre arquitectura e design, assim como a ecologia e a geografia. Existe paralelamente uma constante pesquisa em torno das questões de percepção e dos processos de criação de uma imagem. Utilizando uma miríade de referências que vão da arte conceptual à música erudita, da ficção científica à tecnologia mais avançada, na presente exposição Miguel Soares apresenta um universo visual que gira em torno da Geografia, da Geologia e da Luz. ”Geolux” reúne obras com diferentes preocupações e temáticas datadas entre 2006 e o presente e apresentará dois vídeos inéditos que propõem, com base em composições musicais criadas pelo artista, uma animação 3D que foca a reacção de objectos abstractos ao som. Se aparentemente as suas obras propõem sistemas paralelos, quer sejam artificiais quer sejam fictícios, na verdade, a sua intenção é a de propor uma nova forma de conceber a realidade e de alterar a percepção desta. Neste sentido, as suas obras sugerem um novo modo de pensar e de ver o mundo. A obra de Miguel Soares tem um lugar singular na criação contemporânea portuguesa. Diversa e profundamente criativa, é capaz de simultaneamente apresentar situações de uma enorme simplicidade, como aquela em que mostra os locais onde o artista conceptual Bruce Nauman expôs no ano de 2007 (Jumping Nauman, 2007), ou lâmpadas de jardim transformadas em planetas através do simples manipular da abertura do diafragma (Planets, 2008) até à morosa e complexa desconstrução do Concerto de Brandeburgo e a criação de uma nova música que comprova o autismo do seu interprete mais famoso Glen Gould (untitled (Playing with Gould playing Bach), 2007). Miguel Soares foi o vencedor do Prémio BesPhoto 2007 e o seu trabalho de vídeo foi alvo de uma exposição antológica na Culturgest nesse mesmo ano. Albano Silva Pereira .

Cosmografia do Deslumbramento e do Lixo, Rocha de Sousa2008.Nov

link to original post: http://rochasousa.blogspot.com/2008/11/cosmografia-do-deslumbramento-e-do-lixo.html Cosmografia do Deslumbramento e do Lixo Há cerca de cinquenta ou sessenta anos a revista «Colliers» já publicava, pelo imaginário de van Braun, largos conjuntos de projectos dedicados às viagens no espaço cósmico, ou pelo menos entre os planetas mais próximos do Sistema Solar. Alguns desses projectos inspiraram, por fraccionamento, as verdadeiras pistas das primeiras cápsulas tripuladas (com vantagem para os soviéticos, nessa altura) e as possíveis viagens entre planetas. A prudência tecnológica, e as próprias limitações orçamentais, conduziram ao estudo de sucessivos rastreios comandados à distância, usando satélites artificiais capazes de orbitarem a Lua, Venus ou Marte, fase em que se acedeu a importantes conhecimentos sobre esses astros, tendo em conta cartografias decisivas e detecção dos componentes da armosfera, do solo, de uma grande variedade, aliás, de acções robóticas relativas a espectros químicos, por exemplo, cujos resultados eram enviados para a Terra. Pelo uso posterior, ou a par destes métodos, de sondas com meios de aterragem, movimentação e pesquisa, hoje já se pode defender que conhecemos praticamente todo o planeta Marte, além de estarmos cada vez mais informados sobre Vénus, Mercúrio, Júpiter ou Saturno, com exploração paralela dos vários satélies desses astros. De resto, ao lado desta programação que acabou por se estender até ao limite do Sistema Solar, além de sondas atiradas para o infinito, através da nossa Galáxia, o homem foi cumprindo um trabalho de avanço até à Lua, acabando por fazê-lo por intermédio do Projecto Apolo e de sucessivas viagens com astronautas que não só alunaram como trabalharam na superfície do nosso satélite. Todo este conjunto de acções no espaço exterior à atmosfera terrestre, incluindo uma possível viagem até à superfície de Marte, precisa cada vez mais, no território do nsso planeta e em estações orbitais de carácter experimental e logístico, com astronautas permamentes, trocados em tempo próprio, o que se preparou, agora numa colaboração entre os mais avançados países ligados à exploração do espaço, com instalações entretanto já caducadas. Passou-se para a junção modular de nova concepção, habitáculos com gente a bordo, em rotação, sobretudo pela criação das recentes naves mediadoras, «Vai-vem». Essas naves de ida e vinda transportam vários astronautas, possindo um grande porão, apropriado, para carregamento de partes diversas, muito material de construção ou de sobrevivência, em ordem a cumpir as fases estruturantes da Estação em órbita, à qual atracam os cargueiros/mensageiros, cujos tripulantes convivem com os «residentes», fazendo, por intermédio de um grande braço móvel das naves mediadoras, o transbordo das mercadorias desse ponto para lugares estratégicos, na proximidade do ponto de montagem. Ao longo de todo este tempo, várias décadas, os estrategas de diferentes especialidades, passaram a controlar uma imensa rede de satélites robóticos que giram em torno da Terra, segundo diversas rotas, permitindo alertas de defesa, redes de comunicação e vigilância, a par de outras vias que são mais votados a experiências de retorno. A imagem aqui publicada, de grande realismo, «imita» certas fotografias tiradas no espaço e em circunstâncias semelhantes. Este género de estações eram as «anunciadas» na «Colliers», nos anos cinquentam, e cujo modelo Kubrick usou no seu filme «2001, odisseia no espaço». Quase tudo, nesse filme, fazia parte de uma invenção decalcada em projectos «possíveis». Mas as chamadas Plataformas de Anel foram por enquanto abandonadas. Tarkoski realizou o seu filme «Solaris» num cenário a condizer com esse tipo de instalação cósmica, embora procurando, entre ruínas e lixo abandonado, desenvolver profundas reflexões sobre o homem, sua existência e situação no Universo. A figuração plástica que nos propõe Miguel Soares reveste-se, para além da sua singularidade enquanto espectáculo, a um tempo histórico do futuro no qual Plaraformas com esta confiuguração anelar, meio construídas ou meios desconstruídas teriam uso. Pode tratar-se de um desastre futuro, lixo em volta da constrção arruinada, assim destinada a vogar no silêncio até qualquer possível aproximação e queda na Terra. Mas as fases de construção chegam a parecer espectáculos assim. Os astronautas engenheiros não pousam as suas «caixas de ferramentas» numa mesa a seu lado, mas apenas no vazio e perto de si. Daqui e dali se recolhem peças, ferramentas, cabos, ligando o que há para ligar, encaixes, desperdícios de facto, consolidação dia a dia, semana a semana, ano após ano. E o que é mais inquitetante é o facto de uma rota orbital diversificada estar hoje carregada de satélites artificiais, restos de naves e de peças, caixas provisórias, tudo na mesma linha de comportamento que foi enchendo o nosso habitat dos mais diversos lixos, vulgares ou cada vez mais perigosos. Os mesmos erros além do horizonte. E talvez um dia, num local longínquo, colonizado pelo homem, espécie superior mas de difícil adaptação a uma profunda mudança de sentido e medida, dado a esta à sua mania de crescimentos apocalípticos. Rocha de Sousa A estreia nacional das alegorias electrónicas de Miguel Soares, Nuno Crespo2008.Nov

link to original article: http://dn.sapo.pt/inicio/interior.aspx?content_id=1134155 Primeira exposição individual do artista num museu português O trabalho de Miguel Soares faz parte da geração dos anos 90, não porque começa a expor activamente nessa década mas porque os princípios a partir dos quais constrói o seu trabalho se integram numa procura de novos referentes culturais e processuais nas artes visuais que são comuns a essa década. Esta exposição, como escreve o comissário Miguel Wandschneider, “corresponde a um acto de reconhecimento de um dos artistas mais idiossincráticos e com um universo obsessional mais singular no contexto artístico português das duas últimas décadas.” A obsessão do artista prende-se com a possibilidade de construir um universo baseado unicamente na possibilidade ficcional e artística dos dispositivos electrónicos e virtuais. O mundo que constrói tem referências na cultura juvenil e no imaginário da ficção científica. Referências estas provenientes não da típica banda desenhada impressa mas da ficção tal como presente no jogos de computador e na realidade virtual. O mundo que se vê surgir nas animações 3D de Miguel Soares é uma tradução do mundo da vida, dos gestos quotidianos e das suas tensões políticas e sociais. O mundo artificial ficcionado pelo artista já não pertence à herança moderna e inscreve-se num terreno que se situa depois do mundo contemporâneo, o que acontece nestas alegorias electrónicas afasta todas as possibilidades de reconhecimento entre o que aí se passa e os acontecimentos mundanos. O homem que se vê surgir a três dimensões nos ecrãs de Miguel Soares perdeu o contacto não só com a natureza mas com a própria ideia de humanidade dentro e fora de si. O traço mais humano destes trabalhos é a utilização que o artista faz da música e que cria uma camada sentimental e poética em torno destas imagens que doutro modo seriam frias e distantes. A experimentação da imagem a que se assiste nos seus vídeos e animações são sempre acompanhadas da apropriação de músicas e sua manipulação (Tim Buckley, James Whale ou os Sack & Blum têm presença neste universo 3D). O dispositivo digital é não o que permite a construção das obras do artista, como é instrumento de crítica política. Temas como o lixo espacial que se acumula no universo e cujas consequência ninguém sabe bem determinar (SpaceJunk de 2001), a guerra fria entre os EUA e União Soviética abundante em discursos de poder (Time Zones de 2003) ou a grande alegoria da origem do homem e do planeta (Place in Time de 2005) são pilares que suportam a actividade de Miguel Soares e que a resgatam de ser gestos meramente lúdicos e estéreis de um ponto conceptual e/ou social. É uma exposição difícil porque obriga o espectador à aprendizagem de uma linguagem nova, com regras diferentes e com resultados nada habituais nos discursos correntes da cultura visual contemporânea.

Tags: 2008, Culturgest 2008

Imagens, sons e música, José Marmeleira2008.Nov

link to original page: http://ipsilon.publico.pt/artes/critica.aspx?id=213015 Animações 3D e vídeos de Miguel Soares exploram as relações entre imagens e sons. Quando descemos até as galerias da Culturgest, onde repousam as animações 3D e os vídeos de Miguel Soares (Braga, 1970) escondidas pelas paredes, a primeira sensação é a de que chegámos a um lugar habitado por sons associáveis ao cinema, à música ou ao jogos de computador. Situações semelhantes são evocadas nas obras expostas, mas assim que o confronto com estas se materializa, diminui a possibilidade de reconhecimento e diversão: as imagens de Miguel Soares não são muito acolhedoras e estão longe de ser previsíveis. Comissariada por Miguel Wandschenieder, a exposição centra-se numa retrospectiva de animações 3D desenvolvidas pelo artista, entre 1999 e 2005, e inclui também três vídeos. A especificidade da selecção (Miguel Soares trabalha igualmente com outros meios, como a fotografia e instalação) oferece a este núcleo de obras o seu contexto expositivo “original” e familiariza o público com uma realidade incontornável: a presença da cultura popular, na sua acepção mais contemporânea, na prática dos artistas nacionais. Algumas animações remetem para situações próximas do imaginário da ficção científica (”Place in Time”, 2005), outras desenham um olhar poético e perscrutador sobre diferentes realidades (o espaço em “SpaceJunk”, de 2001, a história política, em “Time Zones”, de 2003). A figura humana está quase sempre ausente ou surge como uma abstracção, uma memória visual numa profusão de arquitecturas e paisagens. Talvez por isso, mais do que narrarem histórias, algumas obras de Miguel Soares documentam contextos ou situações hipotéticas, como a vida de um planeta (outra vez “Place in Time”) ou os avanços tecnológicos em “Archibunk3r Associates” (2000), autêntico portfólio audiovisual de projectos de tecnologia de ponta. Ora o que torna singular esta apropriação de diferentes registos audiovisuais (documentário, apresentação publicitária, jogo de computador) é o modo como nela surgem integradas diversas técnicas cinematográficas (movimentos de travelling ou planos-sequência): o resultado é uma interrogação à nossa experiência das imagens. A este facto não é alheio o conhecimento da linguagem do 3D, cuja aprendizagem o artista iniciou nos finais dos anos 1990, bem como a familiaridade com o cinema. Algumas animações, porém, parecem toscas, quase anacrónicas, traindo uma abordagem amadora e intuitiva (ligada à ética Do-It- Yourself ). Não se deve, portanto, falar de um virtuosismo, mas antes de um labor quase artesanal, de amadorista (no sentido de alguém que cultiva uma arte), pleno de invenção e exemplificado nas manipulações de “Your Mission is a Failure (MechWarrior 2)”, de 1996, ou nas relações entre imagens e sons de “Time Zones”. E aqui chegamos a um dos aspectos marcantes deste núcleo do trabalho de Miguel Soares: o som. Em algumas animações são as imagens que dão origem a uma banda sonora (”SpaceJunk”), noutras foi a música que esteve primeiro, como acontece em “GT”, de 2001, uma das melhores obras em exposição. Os repertórios usados cobrem diversos géneros e ferramentas musicais (colagens, samples) e revelam uma correspondência subtil com aquilo que os ecrãs mostram. Outro aspecto sobressai: a consciência da energia significante da música, por exemplo, no vídeo “Untitled” (two), de 1999, onde temas do primeiro disco de Tim Buckley servem de “banda sonora” a uma situação registada pelo artista no seu apartamento: uma discussão na rua seguida de agressões físicas. E assim – num percurso possível pela exposição – acabamos confrontados com uma irrupção do real. Que se encontra com os mundos virtuais das animações.

Tags: 2008, Culturgest 2008

Miguel Soares, 3D Animations and Video Works 1999-2005, Culturgest, Lisbon2008.Oct

Miguel Soares opening October 17th, 2008, 10PM list of works:

Miguel Soares (Lisbon, 1970) has been producing work since the early 1990s that reveals a fascination with futuristic utopias, technological innovations and the iconographic universe of science fiction. Initially, this fascination took the form of appropriating and manipulating pre-existing photographic images, as well as using references and conventions from the field of equipment design, firstly taken as a referent at the level of the photographic image and then transposed to the formal conception of the works. In the second half of that same decade, much of the artist’s activity resulted in the production of highly interactive sculptures and installations, which represented characters, environments, situations and objects belonging to hypothetical science fiction worlds. It was during this phase that the artist began to use video as a medium for projecting animated images, working at first with pictures drawn from computer games and then with other images created in 3D from graphic elements available on the Internet. In the first few years of his career, his work met a positive critical reception, but it was with his 3D animations that it reached full maturity. It is precisely this facet of his work that this exhibition now seeks to illuminate.

images below: courtesy of miss dove.

Exhibition catalogue by Atelier Carvalho Bernau

. Some Remarks on the Work of Miguel SoaresMiguel Wandschneider Both Miguel Soares’ work and his artistic career, since he first burst onto the artistic scene at the beginning of the 1990s, can be contextualised in generational terms and, more specifically, he can be seen as part of a constellation of artists from the same generation who mostly studied at the Lisbon School of Fine Art. As frequently happens with each generation, in those first crucial years when people’s aesthetic and ideological stances are defined, and at a time when their careers have not yet become individualised, these artists shared a series of values, attitudes and concerns that established a territory of affinities and provided them with concerted strategies of action. Deeply imprinted on the practices of this constellation of artists, and clearly evident in Miguel Soares’ work, were the rejection of the traditional disciplines (and painting in particular), a fondness for references originating from a globalised contemporary cultural landscape, namely both the mass culture and the youth cultures with which they identified, and, with varying degrees of political intentionality, an interest in questions and themes related with the contemporary world. At stake was not only their openly declared reaction to their experience (traumatic for many of them) as students at a stiff and somewhat stuffy art school, where they were closed off from artistic contemporaneity[1], but also their total lack of identification and their clear demarcation from the modes of production that had shaped the artistic scenes in the course of the 1980s. It is perfectly obvious today that, in keeping with the dynamics to be noted in the international context, the generation that emerged in the first half of the 1990s played a fundamental role in accelerating and consolidating an artistic paradigm shift that had been in progress since the 1960s and which we can briefly classify on the basis of two factors: on the one hand, the loss of hegemony (which does not mean a loss of relevance or legitimacy) of the traditional disciplines as a framework that can be used to integrate artistic practices; on the other hand, the opening up and externalisation of artistic practices in relation to the most diverse systems of cultural and symbolic production and fields of reality, definitively surpassing the modernist canons and their conception of art as an autonomous activity with its own reference system. Miguel Soares’ oeuvre, built up over the last twelve years, identifies him as one of the most idiosyncratic Portuguese artists, with one of the most singular and obsessive universes of the last two decades. From a very early date, his work began to reflect his fascination not only with the imagery and iconography of science fiction, but also with the artificial atmospheres in which life unfolds in the technologically advanced societies and with the vertiginous pace of modern-day technological development, which plays such a decisive role in mediating and transforming our experience of reality. Such fascination has inevitably laid down the limits of what, at least so far, may be identified as the thematic hard core of his work, albeit with very diverse variations and without this being allowed, as has so frequently and rather hastily been supposed, to exhaust the questions and subjects explored by the artist. In 1992, when Miguel Soares held his second solo exhibition, this fascination of his was already perfectly recognisable. One might, for example, remember the series of eight photographic diptychs presented at that exhibition, juxtaposing reproductions of sepia images, dating from the 1950s and 1960s, of vehicles (car, propeller, plane, flying saucer), with colour images of domestic interiors in the 1960s, equipped and furnished according to the aesthetic patterns that have since endured as a memory of the interior design of that time. In this way, the artist drew our attention to the fact that the growing enhancement and generalisation, throughout the 20th century, of the house as the locus of social and, in particular, family life was accompanied by the euphoric desire for, and increasing possibilities of, mobility within the territory and the conquest of space. One could also refer, in passing, to the set of furniture-sculptures that he presented at his next solo exhibition, two years later: each of these pieces (bookshelves, sideboards, filing cabinet, bed, television stand and screen) incorporated a light box with a manipulated photograph of a terrestrial landscape over which UFOs can be seen flying. Appearing simultaneously as both furniture and sculpture, both utilitarian objects and works of art (vaguely evoking the tradition of minimalist sculpture and, in particular, certain sculptures by Donald Judd), these pieces reflected, in an ironic and undramatic fashion, the already mentioned loss of autonomy of the art that the modernist paradigm had advocated, as well as the closely related phenomenon of the aestheticisation of everyday life, which is omnipresent in contemporary societies. In those years, Miguel Soares’ work was still heavily marked by the circumstances of his artistic education – between 1989 and 1991, he studied photography and attended, at that same time, a course in equipment design, chosen less as a vocation than as an escape from the teaching of painting or sculpture, which he saw as a dead end. From 1995 onwards, the use of photography as a medium lost its central importance, although it did not disappear from his work, even reaching the point of its recently earning him the distinction of winning the BES Photo Prize. Design also lost importance as a field of references for him, even if his earlier questioning of its status and of works of art that simultaneously exist as functional objects reappears, with renewed effectiveness, in Celulight (1999), a set of lamps made from the recycling of the brightly-coloured plastic packages produced at that time by the Portuguese mobile phone companies and thrown away each day in large numbers. What is more interesting for the purposes of this text than simply noting that, in his early years, photography represented the principal medium of his work, is to emphasise the fact that the use that he made of it was systematically linked to the re-use and manipulation (digital after 1994) of pre-existing images. In fact, Miguel Soares was one of several artists from his generation who adopted different strategies of appropriation in the creative process with absolute naturalness. It was not long before his own acts of appropriation began to include mass-produced consumer objects, images and sounds from computer games, graphic features and images taken from the internet and musical themes (used on the soundtrack of many of his videos and 3D animations). Like so many artists of his generation, Miguel Soares was aware of the legal impediments to re-using, for artistic purposes, materials that had been produced and distributed within the field of the cultural industries, a question that became an urgent one in the 1990s with the dissemination of the video as an artistic medium and the consequent proliferation of works that took film and music as their sources for appropriation. It was precisely this question that, in 1994, he touched on in his first video, Copyright Law. Consisting of a cascade of hundreds of images spliced together from television and video cassettes, and having as its soundtrack (and exempted from copyright) the work Crosley Bendix discusses the Copyright Act (1992), by Negativland, the video was conceived as a visual illustration of that passionate manifesto issued in defence of the free access for artistic purposes to images and sounds that are circulated through the mass media, subject to severe restrictions imposed by the cultural industries under the protection of purely economic interests. The images were edited using two VHS recorders, employing cut and paste procedures that were analogous to the composition technique recurrently used by the group – the sticking together of fragments of magnetic tape that had been cut with a razor blade. In the second half of that decade, Miguel Soares’ activity was to increasingly take place outside the clearly demarcated and stable disciplinary parameters. A significant part of his work, in that period, took the form of sculptures and installations, made with mass produced materials and simple technological devices, which represented characters, objects, atmospheres and situations belonging to hypothetical worlds from science fiction. For example, in Vr Trooper (1996), we come across what we suppose to be a futuristic station used for observation or surveillance: a robot with a military appearance, seen through a surface of red plexiglas and under strobe lighting, makes rotating movements inside a metal cylindrical capsule, itself standing on turf. Immediately afterwards, in Heaven’s Gate (1997), the artist sought to recreate the collective suicide of the members of a religious sect (whose name was given to the title of the piece) at a ranch in San Diego, in California, when a comet passed through the sky in March 1997. The installation simulates several bodies, either asleep or dead, that can be found lying on shelves, covered by purple satin sheets and wearing trainers of the same brand. The sheets gained greater volume under the effect of the air blown into them by electric fans connected to movement detectors, after which they returned to their former state of rest. In this way, the moment was suggested when the members of the sect, in accordance with the belief that led them to commit suicide, were teletransported by a space ship to another planet. In turn, Beep (1998) constructs the image of a flying saucer emitting a red light in a circular movement, as if it were reconnoitring the surrounding space – the sculpture reacts with light effects both to the sounds that it picks up and to the sound that it produces, static noise interrupted every minute by a beep. This piece attained its greatest expressive force in the space of a former water tank in Madrid, where it was presented for the first and only time. During this period, Miguel Soares used a rudimentary video card (the Creative TV Coder of Windows 95) to record sequences of images and sounds created from the manipulation of computer games. The two works of this nature that he produced, Your Mission is a Failure (1996-97) and Barney Online (1996-98), different versions of which were presented in those years, open up the imagery of science fiction, already perfectly recognisable at that time, to the iconographic universe and aesthetic codes of computer games and futuristic cartoons, foreshadowing the 3D animations to which he so intensely devoted himself from the end of that decade onwards. Your Mission is a Failure records a series of performances by the artist in the virtual environment of some computer war games (including MechWarrior 2, Dark Forces, Doom, Descent 2 and Duke Nukem 3D). Recorded in real time, these performances relate various specific actions dissociated from the logic of these games, such as, for example, continuously dying (hence the title of the work, which corresponds to the message of the computer game Command and Conquer when the player fails in his mission), becoming immortal, exploring and going beyond the frontiers of the scenic space of the games, or making music with the respective sounds. The fragmentation and pasting together of images and sounds that have been decontextualised from the narrative plot inherent in the games, as well as the playful exploration of the possibilities and limits of the games outside the protocol and objectives that they propose, arouse in the spectator a feeling of strangeness that is exacerbated by moving from the virtual environment of the computer to the wall of the exhibition space, where the videos are projected in large formats. In a second and shorter version of this video, the crucial importance of the sound in creating this feeling of strangeness was reinforced by positioning in the centre of the projection a psychedelic light box (reused from a solo exhibition in 1996), which reacted to the sound through a sensor. In the videos made from computer games, Miguel Soares found a way to bring to his work what at that time was one of his favourite recreational activities, having reached the point of spending several hours a day playing and interacting in front of the computer. Even more flagrantly than in the previous video, Barney Online provides an eloquent testimony to the crossover between artistic practice and a certain playful activity that is accompanied by an aesthetic investment. In the case of this latter video, that activity also involved participation in a reference group with repercussions on the construction of the artist’s personal and social identity, in the context of a youth subculture with specific codes, values and rules. This video subjects the spectator to a cascade of violent images and sounds that we recognise as having been taken from one of these computer games in which, in order to survive, the character/player has to annihilate the enemies that keep appearing in his path as he moves along a labyrinthine bunker. The video joins together excerpts from the virtual performances of a character (Barney), embodied by the artist, over roughly two years in the Internet game Quake TeamFortress, as a member of the largest and oldest clan (he got to be one of its leaders) who in Portugal, as in many other countries around the world (most of them numbering between 10 and 40 members), dedicated themselves daily to playing this game, establishing their own rules for the admission of members, as well as for the organisation and functioning of the clan. The brief messages that run along the upper strip of the images provide additional clues about the nature of the events and situations that are documented, but these remain obscure for most people, who are not familiar with the codes that are only accessible to those who have been initiated into the game. The decontextualisation of the images and sounds is, in this case, also largely dependent on the fact that the performances took place, not during the playing of the actual game, but in situations of convivial interaction with members of his own and/or other clans. What is imposed on the spectator is the hypnotic flow of a display of colossal violence. This video confronts the spectator with a cascade of violent images and sounds that we recognise as having been taken from one of these computer games in which, in order to survive, the character/player has to annihilate the enemies that keep appearing in his path as he moves along a labyrinthine bunker. The video joins together excerpts from the virtual performances of a character (Barney), embodied by the artist, over roughly two years in the Internet game Quake TeamFortress, as a member of the largest and oldest clan (he got to be one of its leaders), who in Portugal, as in many other countries around the world (most of them numbering between 10 and 40 members), dedicated themselves daily to playing this game, establishing their own rules for the admission of members, as well as for the organisation and functioning of the clan. The brief messages that run along the upper strip of the images provide additional clues about the nature of the events and situations that are documented, but these remain obscure for most people, who are not familiar with the codes that are only accessible to those who have been initiated into the game. The decontextualisation of the images and sounds is, in this case, also largely dependent on the fact that the performances took place, not during the playing of the actual game, but in situations of convivial interaction with members of his own and/or other clans. What is imposed on the spectator is the hypnotic flow of a display of colossal violence. From the mid-1990s onwards, and with even greater emphasis towards the end of the decade, when a completely new generation began to emerge, a growing number of young Portuguese artists adopted video as a medium. In fact, video offered an extremely attractive alternative to the traditional media, proving itself to be particularly effective for artists who were interested in broaching and commenting upon aspects of contemporary reality, constructing fictional narratives, exploring performative situations, examining the influence of time as a mediating factor of perception, or incorporating references from an expanded cultural landscape, with particular emphasis being given to film and music. In an initial phase, videos were made using cameras that filmed in the Video 8 or Hi8 format and two VHS or S-VHS reproducers , this being the equipment that was available at that time and which very soon became obsolete as a consequence of the breakneck speed with which technological changes were being introduced, accompanied by their immediate democratisation. The introduction onto the market of increasingly sophisticated digital cameras and computers at accessible prices, as well as software that was easy to use for the editing and post-production of images and sounds, created extremely favourable conditions for the use of video in artistic production, exponentially increasing the creative possibilities and the quality parameters that were now within reach of artists, without the need for them to rent equipment or to seek the help of professionals. Considering the great fondness that he felt, from the very outset, for technological devices that were characteristic of the period and accessible to non-professionals, it is not surprising that Miguel Soares was one of the first Portuguese artists of his generation to work with video. However, while many of his peers centred their artistic practice on that medium, he made a quite different and atypical choice, preferring to use 3D animations as the quintessential arena for his work from the end of the 1990s onwards.[2] The genesis of these works dates back to a project that he developed between 1996 and 1998, in parallel with the videos and installations I mentioned earlier: using what today is an obsolete computer (the Pentium 166mmx) and a very basic 3D modelling programme based on the use of simple geometrical forms (Corel Dream 3D), the artist built and made small animations of a virtual city (X-City) whose size and complexity he intended to progressively expand as he transferred the file with the model of the city onto increasingly faster personal computers that would greatly speed up the whole process. As it did not take him long to realise, the tools that he had chosen to perform these first experiments with animation were manifestly not up to the task – the animation had to be done manually, frame by frame, before passing through an extremely slow process of rendering (converting the 3D model into final images). In 1999, before he definitively abandoned the project, and at a time when the rendering of each frame was taking him as long as 13 hours, Miguel Soares recovered the model of the city in order to make Y2K, his first work of 3D animation to be presented publicly. Remaining faithful to his persistent do-it-yourself attitude, Miguel Soares began to use not only computers with an ever greater processing capacity, but also non-professional 3D modelling and animation software, which, despite its being very basic, offered him much greater possibilities for figurative composition. More precisely, he was able to make progressively more complex versions, with new functions and greater quality, of a programme designed for the construction of landscapes and environments (Bryce) – with which it was also possible to incorporate models of objects imported from the Internet – and of another programme that enabled him to model and animate human figures (Poser). In this way, the artist found himself engaged in an extremely laborious and painstaking process – he spent between six months and a year working intensely on making each of the animations that came after Y2K. All of this required him to undertake a programme of constant learning and self-teaching, experimenting constantly with the creative possibilities of these tools. The 3D animations to which Miguel Soares so stubbornly devoted himself from 1999 to 2005 comprise an undeniably singular oeuvre displaying a remarkable range of formal solutions. Condensed within these fictional narratives is a painstaking work of figurative composition and the careful film-based construction of points of view, camera movements and sequences, calling for a remarkable control of cinematic time. No less crucial in determining the involvement of the spectator is the organic relationship that is established between image and sound. Making the most of his very particular musical erudition, his profound knowledge of the sounds of his generation and his familiarity with a very eclectic repertoire of references in this field, Miguel Soares constructed the soundtrack of his animations from music played in many different styles (Tuxedomoon, Combustible Edison, Funki Porcini, Sack & Blumm, Roberto Musci & Giovanni Venosta, Negativland), but also, from 2002 onwards, from themes that he himself composed, based on his manipulation and sequencing of samples taken from the Internet, television, films or music (in this period, firstly in 2002, and then later in 2006, he published two CDs of his own music). In many of these works, Miguel Soares pursues his interest in themes from the contemporary world, whether or not these are filtered through an imaginary projection into a more or less distant, but entirely plausible, future: the spectre of militarisation and totalitarianism (Time for Space, 2000), the anonymity and atomisation of life in the large cities, as well as the loss of our direct relationship with nature (Archibunk3r Associates, 2000), the increasing pollution of the skies and seas (SpaceJunk, 2001, and H2O, 2004, respectively), the cold war between the United States and the Soviet Union (TimeZones, 2003), or the survival of the human species and its capacity for adaptation, dating from remote times and continuing into a distant post-apocalyptic future, faced with natural catastrophes or the mass destruction caused by large-scale wars (Place in Time, 2005). Running through all these works is both a sombre perspective and a feeling of melancholy that, nonetheless, manage to avoid creating a denunciatory rhetoric with moralistic overtones. With these 3D animations, Miguel Soares’ work reached full maturity and established for him a prominent position in the Portuguese art world. The exhibition at Culturgest with which this publication is associated has, as its central core, a retrospective look at this facet of his work. As we makes our way through the exhibition, this central core, composed of six works, is preceded by the presentation of two videos [Untitled (Two), 1999, and Expecting to Fly, 1999-2001] in which the artist films in a “voyeuristic” fashion, and poetically transforms, real violent situations that were to dramatically interrupt the nights that he spent in front of the computer. Besides this “realistic” counterpoint to his 3D animations, the exhibition also includes a kind of flashback at the end, with excerpts from the first video that he made based on computer games, Your Mission is a Failure. Since this is Miguel Soares’ first solo exhibition on the institutional circuit, it corresponds to the recognition of the singularity and relevance of his work, but also to a gesture of encouragement to an artist who has persevered under difficult conditions and of whom we believe that we can safely say that his best work is yet to come. [1] In this respect, it is interesting to quote the artist himself: “During my years at the Lisbon School of Fine Art, the teaching methods were completely cut off from the contemporary reality that was taking place outside the school. It was as if I and my friends – Pedro Cabral Santo and Alexandre Estrela, amongst many others – were forced to lead double lives, working at the school during the day and, the rest of the time, making plans for exhibitions and discussing art, sometimes well into the night.” This is how the artist begins a commentary on his work Night Art School, from 1995, conceived as a model of an art school engaged in constant, uninterrupted activity. Made from yellow formica and red plexiglas, and placed on a grass-covered base, the sculpture had 24 white lights inside, connected to psychedelic sensors that reacted to the sound of people moving around inside the exhibition space. The light patterns thus formed alternated with excerpts of electronic music (especially Kraftwerk and Negativland). According to the artist, this piece “reminded [him] of Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory. As if it were a scale model of a new experimental art school.” Significantly, the piece was produced for the Wallmate exhibition, organised by Miguel Soares and Alexandre Estrela, which took place in 1995 in the Cistern of the Lisbon School of Fine Art, and brought together a group of artists from their circle of friends and acquaintances, who, like them, were final-year students. According to the artist, the exhibition was conceived “as a reaction to the academic concepts that prevailed inside the school”. All these statements have been taken from the artist’s website at (http://migso.net/artwork/1995/miguel_soares_night_art_school.htm). [2] In 2002, when he was asked the reason for his interest in 3D animations, Miguel Soares replied: “[I’m interested in] working with the technologies that are available to ordinary people and which give them the opportunity to do what previously could only be done with the use of specialised equipment and lots of money. I’m also interested in the fact that, today, a person with a computer that costs about a thousand euros can make music, edit videos and make 3D films, something that [previously] was only possible using computers the size of a truck, which cost thousands of euros per minute in electricity just to run them. Or, in other words, over the last two or three years, in doing my work I have been exploring what an average person can do with an average computer.” cf. “Criar coisas que não existem”, an interview with Sandra Vieira Jürgens, in Arq./A – Revista de Arquitectura e Arte, No. 12, March-April 2002, p. 82. No atelier virtual de Miguel Soares, José Marmeleira2008.Oct

link to original page: http://ipsilon.publico.pt/artes/entrevista.aspx?id=217987

No atelier virtual de Miguel Soares Fazer arte com animação 3D não é habitual no contexto português, mas Miguel Soares é uma excepção e singularíssima. Na Culturgest, em Lisboa, está um núcleo dedicado a esses trabalhos que pede uma redescoberta. Sem receios académicos nem pudores. Miguel Soares (n.1970) é um dos casos mais atípicos do panorama da arte contemporânea portuguesa. A sua prática artística não é determinada por suportes tradicionais nem privilegia o vídeo ou a instalação. Na verdade, e sem que isso signifique a exclusão de outras linguagens (afinal venceu a edição de 2007 do Prémio BES photo), podemos dizer que boa parte da sua obra consiste em animações 3D. Ora, esse é o núcleo de trabalhos (produzidos entre 1999 e 2005) que está, a partir de hoje, ao lado de alguns em vídeo, na Culturgest, em Lisboa, numa exposição comissariada por Miguel Wandschneider. A maioria conta ficções e narrativas animadas que, escreve o comissário, “condensam um aturado trabalho de composição figurativa e uma cuidada construção fílmica de pontos de vista, movimentos de câmara e sequências, com um assinalável controlo do tempo cinematográfico”. Mas o cinema não é o único elemento identificável na animação 3D de Miguel Soares. O legado visual da ficção científica e dos jogos de computador assomam até de forma mais visível e também a música marca presença como forma de criar ambientes, potenciar a imersão do espectador, criar realismo ou alterar o ritmo e ordem de um vídeo. Música que tanto pode ser uma canção de Tim Buckley ou uma faixa dos Negativland. Ou do próprio artista, também ele um compositor de temas e bandas sonoras feitas com samples da Internet, televisão, filmes ou outras músicas. Composta por três núcleos, esta exposição vem revelar (de novo) um artista cuja obra exemplifica não só o uso do computador, da Internet e da animação digital como ferramentas legítimas da criação artística, mas um momento em que a arte portuguesa se viu forçada a abrir as portas à corrente confusa e indisciplinada da cultura pop e audiovisual. No pátio das Belas Artes O percurso de Miguel Soares enquanto estudante e jovem artista não foi dos mais lineares. Estudou fotografia durante um ano no Ar.Co., experimentou o desenho num atelier da Galeria Monumental e só depois ingressou (em 1989) na Faculdade de Belas- Artes de Lisboa. Aqui, porém, em vez de seguir pintura ou escultura, optou por Design de Equipamento, com o objectivo de trabalhar com materiais como o plástico, o vidro, os metais e a madeira. Tudo menos ficar preso a meios e técnicas tradicionais. Quase 20 anos depois, Miguel Soares tenta explicar as razões para o frustrante encontro: “A minha mãe era guia no Museu Gulbenkian e levava-me para lá aos fins-de-semana. Dos dois aos 10 anos, posso dizer que uma parte da minha vida foi passada entre aquelas pinturas. Por isso, se calhar, quando cheguei às Belas-Artes e descobri nos professores uma versão decadente desse mundo, senti desde logo necessidade de procurar outras referências, não só fora do contexto artístico local, mas também noutros campos que não o da arte.” E não era o único. No pátio da faculdade – uma espécie de microcosmo cultural – junta-se a outros estudantes (e a alguns futuros artistas) para conversar sobre arte, cinema, música, ficção científica e política: “Foi aí que conheci e comecei a conviver com o Alexandre Estrela, o Pedro Cabral Santos, o Tiago Batista e o Heitor Fonseca. Conversávamos sobre o que se passava lá fora, trocávamos ideias sobre os textos que apareciam na ‘Flash Art’ e na ‘Artforum e líamos sobre artistas como Jeff Koons, Ashley Bickerton ou Wim Delvoye.” Os universos exteriores ao mundo da arte também eram explorados. “A música, ou certos acontecimentos políticos como a Invasão do Golfo e, sobretudo, o cinema, com o Kubrick no meu caso, à cabeça. Viemos, aliás, descobrir que antes da faculdade tínhamos partilhado, sem sabermos, as salas da Cinemateca e as sessões especiais do Quarteto.” Quanto à arte portuguesa, os afectos ficavam-se por nomes da geração anterior: “Admirávamos gente como o Fernando Brito e o Pedro Portugal, que tinham feito o curso anos antes. Eram artistas multifacetados, um pouco como o Eduardo Batarda, de que também gostávamos.” Motivados por interesses comuns e vontade em experimentar organizam no princípio de 1990 exposições na galeria da escola. O entusiasmo embateu na indiferença do meio (só em 1995, com “Wallmate”, as coisas se alteraram, ainda que ligeiramente). Miguel Soares teve mais sorte. Em 1991 começou a expor na Galeria Monumental, iniciando uma relação de 11 anos que lhe garantiria a atenção relativa da imprensa. Sem estar submetido a cânones ou à vigilância das hierarquias das belasartes, continuou avesso à pintura (que tinha exposto nos finais dos anos 80) trabalhando em escultura e instalação antes de se deixar fascinar pelas possibilidades dos jogos de computador: “Quando sugiram no mercado já permitiam criar espaços virtuais, mas eram ainda muito delimitados em termos de resolução e qualidade. Acontece que através dos códigos, que apareciam nas revistas da especialidade, descobri que podia alterar a sua natureza, e isso agradava-me.” A descoberta da animação 3D A possibilidade de intervir no espaço virtual, controlando todas as suas variáveis para no fim o recriar, está de algum modo no vídeo “Your Mission is a Failure (MechWarrior 2)”, que prenuncia já o trabalho com a animação em 3D, como se esta fosse uma paleta audiovisual: “Veio permitir-me criar uma simulação, em que controlo tudo, desde a iluminação ao filme, passando pelas câmaras e lugar das personagens.” Um pouco como o pintor solitário no seu atelier? “Nesse sentido sim, mas arrisco dizer que o 3D, pela sua natureza fractal, acaba por ser mais natural que a própria pintura. Afinal funciona sob leis básicas e universais da física e de matemática. Não preciso de misturar tintas para fazer a luz do sol ou uma sombra.” O processo foi, porém, lento e assente na velha ética DIY (Do It Yourself ). Sem formação na área, dedicouse a uma aprendizagem solitária de programas não profissionais de software, experimentando com os meios que tinha à disposição e beneficiando das oportunidades trazidas pela Internet. A sua abordagem revelar-se-ia em Portugal um caso único (e ainda hoje, por vezes, mal compreendido) da relação entre arte e novas tecnologias. Assim, e passada a euforia (seguida da inevitável ressaca) em torno da cyber-art que dominou a segunda metade dos anos 90, como explicar a distância que resiste entre as duas áreas? “Talvez tenha a ver com pouca abertura dos meios académicos”, sugere Miguel Soares. “Sabemos que lá fora há experiências interessantes, como a do Matt Mullicam com o Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), mas de uma maneira o geral os dois campos não se tocam. É raro vermos alguém do design ou das artes interessar-se pela programação ou vice-versa, o que é pena. Gostaria de ter tido a colaboração de programadores. Por outro lado, as galerias e as revistas não se interessam muito por artistas digitais. Limitam-se a ir buscar um ou dois, como o Cory Arcangel e o Miltos Manetas.” Apesar de trabalhar com computadores e imagens virtuais, Miguel Soares não se revê numa posição optimista sobre a tecnologia. Nas narrativas que constituem as suas animações encontramos efabulações inquietantes sobre o futuro da humanidade (”Place in Time”, 2005), alusões à acção do homem sobre a natureza (”Space Junk”, 2001) ou ao fantasma da guerra (”Time Zones”, 2003). A música que as acompanha é outra vertente do trabalho de Miguel Soares, afirmando-o como uma espécie de demiurgo pluridisciplinar interessado em pensar a ilusão das imagens. “É isso que aproxima estes trabalhos da série de fotografias que apresentei no BES Photo: a maleabilidade plástica e manipulação das imagens. O 3D é uma linguagem vectorial que até ser processada e transformada em imagem real, torna as coisas infinitamente escalonáveis. E é essa plasticidade que me interessa para criar objectos, figuras, situações”. Como se estivesse num atelier virtual aberto para o mundo.

Tags: 2008, Culturgest 2008

BES Photo2008.Mar

BES Photo 2007 prize exhibition (winner) exhibited works:

.

A Suspension of DisbeliefA dialogue about the boundaries between representation, fiction, reality and originality. Filipa Ramos: I would like to know more about your training… FR: Are there any coordinates that modelled your present work? I could identify certain elements, like a reflection on what is real, a link between music and images, and an analysis of the mechanisms that regulate and determine perception, but I would like to hear it from you … FR: In fact, it is easy to recognize an interest for design and architecture, especially in the second half of the 1990’s, when you created objects like Racing (1994) or Beep (1998). In the same way, science seems to be a constant. I remember once Pedro Cabrita Reis said that he imagined you as one of those kids that were always playing with robots and carrying out chemistry experiments! FR: Still talking about the use of apparently banal and daily elements, from which one can make new interpretations of what surround us, I would like to know a bit more about your new series Planets, (2008). In this case you used conventional photography to create a series of illusions that are unveiled as we pass through the images … FR: The craters and palindromes portray an almost puerile curiosity to test the reality of things, their possibility of existing in slightly altered conditions. Where is this interest or desire to investigate a subtly distorted reality coming from? FR: Sometimes you seem to take hold of the original images and alter them, recovering, let’s say, a certain primeval state of the elements represented. This is visible both in some of your earlier pieces, and recently in the series where you “remove” a part which had actually been an addition, giving back a more conventional look to the automobile (Liine). How do you characterize this interest in manipulating reality through photography? FR: I find a similar attitude in Untitled (playing with Gould playing Bach) in which the chosen frames gained a certain suspension, between a movement and a static side, which characterizes all the representations of passed, and unrepeatable, elements. You appear to take photographs through the annulation the image’s movement in time. In what way can a picture result from video? FR: In this same video there is a characteristic, which is very present in your work – the relation between image and music. How do you articulate these two elements and how do they coexist? FR: Many of your pieces use elements that touch on the copyright issue and raise questions about the crisis of the current concept of intellectual property. What is your feeling about these problems? FR: You often use digitally constructed images, such as the series of inverted craters, RetarC, or the two videos Place in Time (2005), Sparky (2002) or H2O (2004). In what way are you interested in photography as a means to construct possible inexistent realities? FR: More than using 3D to explore a new media, (and such was the case of digital format when you started using it in the 1990’s), you seem to use it to create photographic situations that you don’t have access to. By this train of thought, these images become digital photographs, also dependent on the photographer’s choice of an exact, unique moment, in which they are captured and crystallised. Do you see your images as photographs or are they closer to traditional pictorial representation, like painting or drawing? Portuguese versionA Suspension of DisbeliefUm diálogo sobre as fronteiras entre representação, ficção, realidade e originalidade. Filipa Ramos: Eu gostava de saber mais sobre a tua formação. FR: Existem coordenadas que foram dando forma ao que é o teu trabalho actual? Poderia identificar certos elementos, como uma reflexão sobre o real, uma ligação estreita entre a música e as imagens e uma análise dos mecanismos que regulam e determinam a percepção, mas gostava de saber por ti… FR: De facto é fácil de identificar um interesse pelo design e pela arquitectura, sobretudo na segunda metade dos anos 90, quando realizaste objectos como Racing (1994) ou Beep (1998). Do mesmo modo, a ciência parece ser uma constante. Lembro-me de uma vez o Pedro Cabrita Reis ter dito que te imaginava como uma daquelas crianças que estavam sempre a brincar com robôs e a fazer experiências de química! FR: Ainda dentro desde uso de elementos aparentemente banais e quotidianos, para a partir deles gerar novas leituras daquilo que nos rodeia, gostaria de saber um pouco mais sobre a tua nova série Planets, (2008). Neste caso recorreste à fotografia convencional para gerar uma série de ilusões que vão sendo desvendadas à medida que vamos percorrendo as imagens… FR: Nas crateras e nos palindromos emerge uma curiosidade quase pueril de testar a realidade das coisas, a sua possibilidade de existência em condições ligeiramente alteradas. Em que reside este interesse ou esta pesquisa por esta realidade subtilmente distorcida? FR: Por vezes pareces pegar nas imagens originais para depois as alterares, recuperando, digamos, um certo estado primordial da condição dos elementos representados. Isto é não só visível em algumas obras mais antigas, como também, recentemente, na série em que lhes “retiras” um pedaço, que já por si era um acrescento, voltando a dar ao automóvel o seu aspecto mais convencional (Liine). Como caracterizas este interesse pela manipulação da realidade através da fotografia? FR: Encontro uma atitude semelhante em Untitled (playing with Gould playing Bach) em que fizeste com que os frames escolhidos ganhassem uma certa suspensão entre um movimento e um lado estático, que caracteriza todas as representações de elementos passados e, logo, irrepetíveis. Pareces fotografar através da anulação do tempo da imagem em movimento. De que modo é que a fotografia pode decorrer do vídeo? FR: Neste mesmo vídeo está presente uma característica muito presente no teu trabalho, a relação entre a imagem e a música. De que modo é que estes dois elementos se articulam e convivem? FR: Muitas das tuas obras utilizam elementos que tocam a questão do copyright e que abordam questões que realçam a crise do modelo actual da propriedade intelectual. Qual é a tua relação com estes problemas? FR: Recorres frequentemente ao uso de imagens construídas digitalmente, como é o caso da série das crateras invertidas, RetarC, ou dos vídeos Place in Time (2005), Sparky ou H2O (2004). De que modo é que a fotografia te interessa como um mecanismo de construção de possíveis realidades inexistentes? FR: Mais do que utilizar o 3D para explorar um suporte novo, como era o formato digital quando começaste a usá-lo nos anos 90, parece que o usas para criares fotograficamente situações que não tens à tua disposição. Estas imagens tornam-se dentro desta lógica, fotografias digitais também elas dependentes da escolha do fotógrafo de um momento exacto, único, em que foram capturadas e cristalizadas. Vês as tuas imagens como fotografias ou mais próximas da representação pictórica tradicional, como a pintura e o desenho? Filipa Ramos: I would like to know more about your training… “Miguel Soares: Present States of Siege” article at Rhizome.org by Miguel Amado2007.Dec

Miguel Soares: Present States of Siege Lisbon-based artist Miguel Soares’ signature 3D animations render virtual realms in which landscapes, characters and objects provoke myriad futuristic fantasies. In ‘Time Zones’ (2003), sequences of collaged images that evoke the Cold War accompany experimental band Negativland’s track by the same title. An engaging allusion to the post-war world order, this work connects what was seen as a permanent state of siege with our current time. Recently, Soares has utilized different technologies to develop his practice, making it less politically charged and more metaphorical. On view until the end of last week at Lisbon’s Museum of Electricity was the installation ‘Do Robots Dream of Electric Art?’ (2007), that consisted of three robots, all equipped with moving heads, tracing red laser beams on the gallery wall in the rough outlines of human bodies. Bringing together Philip K. Dick’s science fiction best-seller ‘Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?,’ in which the main character is an android, with the imagery of cave painting, Soares combines representations of the past and the future into an allegory for present society. Another notable work is ‘Jumping Nauman’ (2006), that is currently featured in the group show ‘Stream,’ presented by New York’s White Box. Using the Google Earth software, this video compiles the exhibition spaces in which Bruce Nauman work was shown in 2006– from New York’s Andrea Rosen Gallery to the Berlin Biennale–thus illustrating the global economy of today’s art scene. A sort of digital appropriation artist ‘fascinated by things that do not exist’–as he once put it–Soares’ output is one of the most significant in the contemporary expanded field of new media, in which concept is taking the place of the once prevailing high-tech fetishism.

Tags: 2007

Do Robots Dream Of Electric Art?, Museu da Electricidade, Lisbon2007.Sep

September 28th > November 25th, 2007 Three moving-head robots are aparently carving a drawing on the wall with red laser beams. scroll down for portuguese version Disco Wall Painting Three “disco” robots (of the “moving heads” variety) trace upon the grey wall the precarious outline of a human On the other hand, the robots are equally beings of a new kind which seem to collaborate here in a remake: in a joint The role played by these robots takes the form of a transferred regression: they are not evoking what they themselves were, but what the men who designed them were once. This piece by Miguel Soares fictionalises the appropriation, by robots, of a founding memory of humankind. That memory does not belong to them: have the beings that created them inserted it, inadvertently or unconsciously, into their programming? We do not know. The title of this piece by Miguel Soares evokes one of the most effective projections of mankind’s fear regarding their own creations, from its Romantic incarnation as Frankenstein’s Monster to the post-modern androids of Philip K. Dick (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, 1968, where Miguel Soares found his title) and Ridley Scott (Blade Runner, 1982). This artist’s vast body of work, which comprises installation and video along with the construction of mechanical and electronic objects, not forgetting the composition of digital images or synthesised sounds, culminates here in the most extreme of metaphors: the automata’s possibility of autonomous action and awareness has led them to resume the evolutionary cultural line of mankind, their original creators. Returning to a logic of caves as iconographic sanctuaries, Lisbon, 12 September 2007

. Versão Portuguesa / Portuguese Version A peça de Miguel Soares ficciona a apropriação, pelos robots, de uma memória matricial da humanidade. Essa Pintura Mural de Discoteca Três robots “de discoteca” (do tipo moving heads) desenham na parede cinzenta a silhueta precária de um ser Por outro lado, os robots são seres também de um novo tipo que igualmente parecem participar aqui num remake: O título desta obra de Miguel Soares remete para uma das mais eficazes projecções dos receios da humanidade em relação às suas próprias criações. Tal receio vem do Frankenstein romântico e passa pelos andróides pós-modernos de Philip K. Dick (”Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”, 1968, de onde Miguel Soares retira o seu título)/Ridley Scott (”Blade Runner”, 1982). A vasta obra do artista, utilizando a instalação e o vídeo, a construção de objectos, mecânicos e electrónicos, a composição de imagens digitais ou sons electrónicos culmina aqui na mais extrema metáfora: a possibilidade de autonomia de acção e consciência dos autómatos leva-os a retomar a linha cultural evolutiva da própria humanidade que os criou. Lisboa, 12 de Setembro de 2007

Histoires Animées, Le Fresnoy, Tourcoing2007.Jan

Histoires Animées Le Fresnoy, Studio National des Arts Contemporains exhibited works: related articles: . Dans SpaceJunk, la désormais classique vision de la Terre depuis un satellite offre Dans Place in Time, sa toute dernière animation, une vallée est parcourue, à travers le temps,

Project for Aleksandra Mir’s Corporate Mentality2003.Nov

Corporate Mentality book download (pg. 162.)

SlowMotion, ESTGAD, Caldas da Rainha2001.May

SlowMotion May 28 > June 9, 2001 exhibited works:

Miguel Soares (1970) estudou Design de Equipamento na Faculdade de Belas-Artes da Universidade de Lisboa, entre 1989 e 1995. Paralelamente, entre 1989 e 1991, frequentou o curso de fotografia da escola Ar.Co, em Lisboa. Encontramos um exemplo claro daquela dupla vinculação logo na série de oito dípticos fotográficos que o artista reuniu na sua segunda exposição individual (”Miguel Soares 1992″, Galeria Monumental, Lisboa, 1992): em cada um destes dípticos, a imagem a cores do interior de uma habitação dos anos 60, mobilada e equipada segundo arquétipos datados de funcionalidade, conforto e apuro estético, surgia justaposta à imagem em tom sépia de um veículo futurista dos anos 50 e 60 (automóvel, hélice, avião, nave espacial), símbolo do desejo eufórico e das crescentes possibilidades de mobilidade no território e de conquista do espaço. Pouco tempo depois, a referência directa ao design de equipamento deslocou-se do interior do plano da imagem fotográfica para a exterioridade material das próprias obras. Corresponde a esta fase um conjunto de esculturas com aparência e funcionalidade de mobiliário (estantes, aparadores, arquivo, cama, móvel de televisor), que incorporavam uma caixa de luz com a fotografia de uma paisagem terrestre sobrevoada por um ovni (”Miguel Soares 1994″, Galeria Monumental, 1994). Podendo ser entendidas ao mesmo tempo como móveis e como esculturas (evocativas da tradição minimalista), como objectos utilitários e como obras de arte, essas peças concretizavam, sem alarido e com eficácia, a inserção da arte na vida quotidiana. Eram também uma proposta irónica de evasão à dimensão utilitária dos objectos e às rotinas do quotidiano através de um imaginário de ficção científica. Os exemplos avançados indiciam uma terceira característica do trabalho de Miguel Soares, que se manteve em grande evidência até hoje: o fascínio pelas utopias futuristas, as inovações tecnológicas e o universo iconográfico da ficção científica. Podemos ser colocados perante a crença nas virtudes emancipadoras do progresso tecnológico, como nas fotografias de cunho retro-futurista atrás descritas, ou os efeitos destrutivos e incontrolados desse mesmo progresso, como em SpaceJunk, animação em três dimensões transferida para vídeo e para imagens sobre papel, actualmente em preparação. Todavia, é sempre pelo lado da imagem e do imaginário que aquele fascínio se declara, indiferente a discursos de apologia ou crítica das sociedades contemporâneas. A partir de 1995, a fotografia como técnica e o design de equipamento como campo de referências perderam centralidade, mas não foram completamente abandonados, na obra de Miguel Soares. As convenções do design ressurgem mesmo, com renovada eficácia, em trabalhos posteriores. É exemplo Celulight, série de candeeiros construídos a partir da reciclagem de embalagens de telemóveis, com que o artista retomou o questionamento anterior acerca da identidade e do estatuto de obras de arte que existem, simultaneamente, como objectos utilitários (”Design Inserts”, “Experimenta Design”, Gare Marítima de Alcântara, Lisboa, 1999). Parte significativa da sua actividade, desde meados dos anos 90, tomou a forma de esculturas e instalações, com forte carácter interactivo, que representam personagens, ambientes, situações e objectos pertencentes a hipotéticos mundos de ficção científica. Estas obras simulam com frequência realidades “high tech” a partir de materiais e dispositivos tecnológicos muito simples, fazendo conviver uma estranheza do ponto de vista formal com um sentido de verosimilhança e plausibilidade na recriação de universos de ficção científica. Esses materiais e dispositivos incluem, por exemplo, lâmpadas, sensores psicadélicos, detectores de movimento, chapas zincadas, relva plástica, espelhos de acrílico, altifalantes, antenas parabólicas, ou um ponteiro laser. Vejamos alguns exemplos. Vr trooper (1996) mostra, dentro de uma cápsula cilíndrica que irrompe pelo chão, um extra-terrestre ou robot, iluminado por uma luz vermelha, que responde ao som ambiente efectuando movimentos circulares sobre si próprio (”Greenhouse Display”, Estufa Fria, Lisboa, 1996; “Miguel Soares 1990-1996″, Edifício da Associação Nacional de Jovens Empresários, Faro, 1996; e “321m2″, Círculo de Artes Plásticas de Coimbra, 2001). Em Heaven’s Gate (1997), instalação inspirada no suicídio colectivo dos membros de uma seita religiosa por ocasião da passagem de um cometa, vários corpos cobertos por tecido roxo e estendidos sobre prateleiras, de tempos a tempos varridos pelo sopro de ventoinhas, supostamente a dormir ou mortos, realizam uma viagem em direcção a outro mundo (”Jamba”, Sala do Veado, Museu de História Natural, Lisboa, 1997; “ARCO 98″, Madrid, 1998; e “321m2″). Beep (1998) representa um disco voador, uma sonda ou um posto de observação, que reage aos sons que produz e aos que capta à sua volta com efeitos luminosos e um movimento circular de reconhecimento do espaço em redor (”Observatório”, Canal Isabel II, Madrid, 1998). Exemplo derradeiro, entre outros possíveis, é Gustavo (1999), um saco amarelo cheio de lixo que emite um feixe luminoso de cor vermelha, enquanto realiza um movimento, deixando inscrito na parede o desenho desse movimento (”Espaço 1999″, Sala do Veado, 1999; e “Miguel Soares 2000″, Galeria Monumental, 2000). É neste período que Miguel Soares começa a usar o vídeo como meio de projecção de imagens animadas, nuns casos retiradas a jogos de computador, noutros casos criadas em três dimensões a partir de elementos gráficos disponíveis na internet. Com essas peças, o imaginário de ficção científica tão característico da sua obra abriu-se ao universo dos jogos de computador e ao dos desenhos animados futuristas. Em algumas obras recentes, o artista documenta de modo “voyeurista”, e desvia poeticamente, situações reais violentas que ele próprio filmou. Umas e outras diversificam as estratégias de apropriação que, no início, se exerciam sobretudo no domínio da fotografia, tendo passado a incidir sobre imagens e sons de jogos de computador, elementos gráficos da internet e músicas de diferentes estilos. Miguel Soares é, entre os artistas da sua geração, um dos que expôs mais cedo a título individual e que conta no seu currículo com maior número de exposições individuais: seis ao todo, cinco na Galeria Monumental (1991, 1992, 1994, 1996 e 2000) e uma, com carácter retrospectivo, na sede da Associação Nacional de Jovens Empresários, em Faro, em 1996. Paralelamente, foi presença assídua em exposições estratégicas na afirmação da geração a que pertence, com destaque para “Independent Worm Saloon” (Sociedade Nacional de Belas-Artes, Lisboa, 1994), “Wallmate” (Cisterna da Faculdade de Belas-Artes da Universidade de Lisboa, 1995), “Greenhouse Display”, “Jamba”, ou “O império contra-ataca” (Galeria Zé dos Bois, Lisboa, e La Capella, Barcelona, 1998). Ainda no capítulo das exposições colectivas, organizadas ou não segundo uma lógica de afinidades e cumplicidades geracionais, vale a pena referir também “Faltam Nove para 2000″ (Galeria da Escola Superior de Belas-Artes de Lisboa, 1991), “20000 minutos de arte no Técnico” (Instituto Superior Técnico, Lisboa, 1994), “Inter@ctividades” (Palácio Galveias, Lisboa, 1997), “Biovoid” (Sala do Veado, 1998), “Observatório”, “Espaço 1999″, “Air Portugal” (”Bienal de Londres”, Shoreditch Town Hall, Londres, 2000), “Gotofrisco” (Southern Exposure, Sister Spaces, Galeria ZDB, São Francisco, 2000), “Comunicantes/Contaminantes” (SNBA, 2000), “Videonica” (Galeria Fernando Santos, Porto, 2001), “Electric House” (”WC Container”, Artes em Partes, Porto, 2001) e “321m2″. Pontualmente, interveio como comissário, ao lado de Alexandre Estrela (”Wallmate”), e como organizador, ao lado de João Simões (”Air Portugal”). “Slow Motion” apresenta uma retrospectiva do trabalho de Miguel Soares com recurso ao vídeo. Na galeria da ESTGAD, são alternadas, numa projecção, duas obras relacionadas com o universo dos jogos de computador: Your Mission is a Failure, que pôde ser vista na Galeria Monumental, em 1996, assim como nas colectivas “Inter@actividades”, numa versão substancialmente diferente, e “Papel de Parede”, no Centro de Arte de São João da Madeira, ambas em 1997; e Barney Online, mostrada, em 1998, nas colectivas “Biovoid” e “Observatório”. Ainda na Galeria da ESTGAD, são alinhadas, numa segunda projecção, as seguintes peças de animação 3d: Time for Space, apresentada já por quatro vezes, primeiro na exposição individual de 2000, depois nas colectivas “Gotofrisco”, “Air Portugal” e “Videonica”; Archibunker Associates, integrada em “Comunicantes/Contaminantes”; e GT, vídeo inédito realizado a partir de uma sequência de imagens que fez parte da peça Play/Pause do grupo Pogo Teatro (Lux, Lisboa, 2001). No espaço da Rua do Hemiciclo, são apresentadas três obras recentes, duas delas inéditas: Untitled (two), já mostrada na Bienal de Faro, no ano passado, Expecting to Fly e Fire!. Your Mission is a Failure 1996 Vídeo, som, cor, 25′ Barney Online, Slipgate Remix 1997 Vídeo, cor, som, 6′32” Time for Space 2000 Projecção vídeo de animação 3d, som, cor, 5′ (loop) Archibunk3r Associates 2000 Projecção vídeo de animação 3d, cor, som, 7′50” GT 2001 Projecção vídeo de animação 3d, cor, som, 4′ Untitled (two) 1999 Vídeo, cor, som, 6′50” Expecting to Fly 1999-2001 Vídeo, cor, som, 3′40” Untitled (fire) 1999-2001 Vídeo, cor, som, 2′54” Da janela de sua casa, segurando a câmara de vídeo na mão, Miguel Soares registou situações violentas que vieram sobressaltar noites passadas frente ao computador: a agressão entre um casal; um carro capotado na avenida deserta, que surpreende uma pessoa durante o seu jogging matinal; e um homem que tenta desesperadamente, e em vão, apagar um incêndio. Com base nestes registos, em tudo semelhantes aos vídeos amadores que as televisões exibem para dar conta de acontecimentos chocantes, o artista realiza três obras em que a crueza da realidade se abre à ficção e ao delírio poético. Miguel Wandschneider |

|